Over 25 years ago I published this piece in Upstate – a regional Sunday news magazine based in Rochester NY. I was a high school American history teacher intrigued with local history. It was published on the 300th anniversary of the raid and filled with references to local landmarks and towns. My goal was to bring little known “international” incident to a largely local audience. (Looking back, I wonder if the subject matter was a bit grisly for the Sunday brunch table). While I’ve had a pdf copy of the original article on my website, I’m posting a text version here to make it more searchable. Despite my relentless overuse of commas, I have resisted re-writing it.

Invaders Came from the North

Upstate Magazine

July 12, 1987

Three hundred years ago, on July 10, 1687, Seabreeze was invaded by the largest army North America had ever seen.

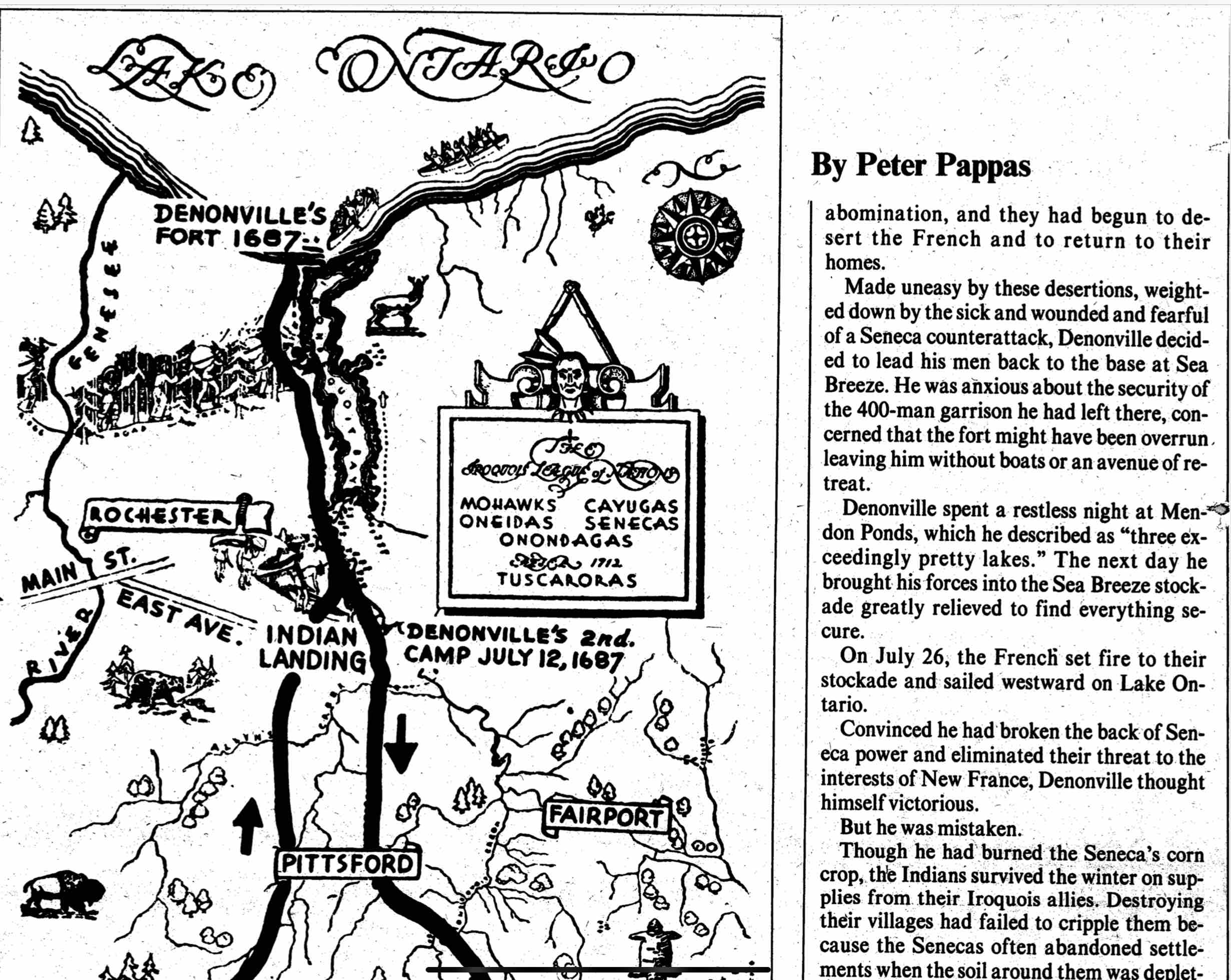

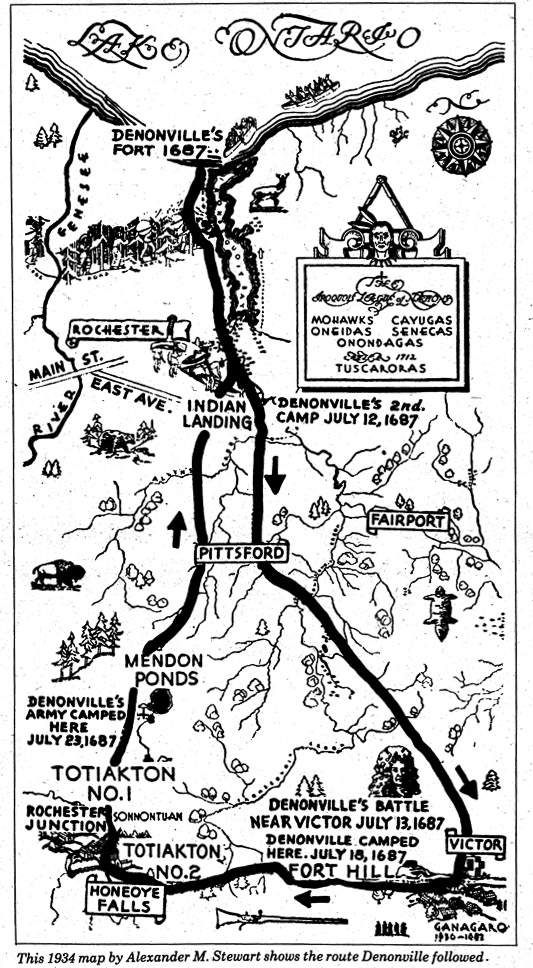

A 350-boat French Armada had left Montréal a month earlier bringing 3000 men and their supplies to the Ontario shore. Their goal: the destruction of the Seneca Indians of the Irondequoit Valley.

Unprepared to meet the invaders, the Senecas sent a small scouting party to the lake bluff at Seabreeze Park. They watched in silence as the French invaders dragged their flat-bottom boats on to the sandbar that today is lined with hotdog stands. On the narrow strip of land that separates Irondequoit Bay from Lake Ontario, the French set about securing their beachhead, and in the next few days built a crude rectangular fort, with a 10 foot high palisade using more than 2000 trees cut from the Webster shore of the bay.

To protect their boats from the Senecas and the intense heat, the French scuttled them in the shallows of the Bay. Soldiers also build scores of ovens to bake 30,000 loaves of bread to feed the troops.

The expedition leader was Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville, son-in-law of one of France’s richest nobleman, an experience military commander and governor of new France, the large struggling colony the French had planted in the New World. It stretched from Montréal in a great arc all the way to the Mississippi Valley in New Orleans.

New France survived on the fur trade, an enterprise which was dependent on the Indians to help trap the retreating supply of animals has the white men push westward. The Senecas served as middlemen, their warriors terrorizing the other Indian tribes of the Ohio Valley to maintain a steady supply of pelts which they traded either to the French in Montréal or the English in Albany, depending on who paid better.

Wedged between rivals, Seneca country had become the political fulcrum of the eastern Indian America.

Because upstate New York was strategically located at the headwaters of the major river systems of the American Northeast, Seneca warriors and traders were able to use the rivers to reach colonists and other Indian tribes over an area of almost 1,000,000 square miles reaching as far south as the Carolinas and as far west as the Mississippi River. Wedged between rivals, new friends in the British colonies of the Atlantic Coast, Seneca country had become the political fulcrum of the eastern Indian America.

Denonville had brought 1500 French colonial troops and 1500 of their Indian allies to the Irondequoit Valley, as he put it, “to enter through the Western chimney of the Iroquois longhouse” to end Seneca interference in French plans for colonizing America.

Jacques-Rene de Brisay, Marquis de Denonville

In the pale dawn of July 13, French troops knelt for Christian blessing as their Indian allies looked on. After breakfasting on bread and creek water they began the final leg of their march on the Seneca villages, following Indian trails which can be traced today by existing landmarks.

They worked their way down the west shore of the bay along what today is Interstate 590, passed Indian Landing near Ellison Park, then marched along Landing Road towards East Avenue. Guided by a map of Seneca trails prepared during an earlier, unsuccessful raid, Denonville was able to move swiftly through the rough territory.

News of the invasion spread quickly among the Senecas as their scouts reported the steady advance of the French columns. The Senecas had at most only 1200 warriors with which to face Denonville, but how many had fled or were elsewhere on raids and hunting parties was uncertain. They understood immediately that the Denonville’s aim was the destruction of their two major villages, Ganagaro, at what is now Boughton Hill, near Victor, and Totiakton, at what is now Rochester Junction, just south of Mendon Ponds Park.

The Senecas weren’t sure which village Denonville would strike first, and with their limited forces, defending both would be impossible. The Seneca strategy was to attack the French forces before they could reach the villages but until they were sure which route the French would take, they couldn’t prepare an ambush.

In their uncertainty and confusion, the Senecas had allowed Denonville’s men to pass safely through the terrain where they would have been most vulnerable – Indian Landing, Palmer’s and Corbett’s Glens. But they knew that when Denonville arrived at the fork where East Avenue meets Allen’s Creek his intentions would be plain – if he went left, he was taking the East Avenue trailed to Ganagaro; if he went right, it was the Clover Street trail to Totiakton.

Seneca scouts saw Denonville take the East Avenue trail and raced to the villages with the news. By then the French were only twelve miles from Ganagaro. The Senecas had almost twice the distance to cover–nearly 23 miles to get to Totiakton and bring its braves to defend Ganagaro.

Determined to reach Ganagaro before the Senecas could reinforce it, Denonville pushed his men mercilessly. As a few Indian women worked the cornfields to suggest the village was still inhabited, the Senecas prepared an ambush. Their hopes rested on a group of warriors hidden in the deep ravine just north of Victor.

Denonville, sword in hand, was clad only in his underwear and boots.

After a forced march of more than 17 miles, the first group of French troops reached the ravine in mid afternoon. Exhausted, they had eaten nothing since breakfast, and in the heat and humidity of the forest that stripped off most of their armor. Denonville, sword in hand, was clad only in his underwear and boots. From the crest of a ridge, they saw below them a small stream which offered enticements of fresh water and rest.

Just as the first soldiers reached the stream, the Senecas struck. The French soldiers struggled to establish a defensive position on the uncertain footing of the steep incline and vast swamp of the Victor Valley. As the Senecas moved in with their tomahawks, it seemed their ambush might succeed, but with the arrival of reinforcements, Denonville was able to rally his troops and drive the Senecas off.

At dusk, one of the French soldiers recorded in his journal the bloody picture of what had occurred. He described how the Ottawa allies of the French butchered and scalped the dead Senecas, then dined on the flesh of their enemies “whose carcasses they had put into kettles” to cook.

On the morning of July 14, it became clear that the Senecas had abandoned their village. But that didn’t deter Denonville. He knew we would have to move quickly and remain constantly on guard against counter attack. To avoid mistaking his Indian allies for Seneca warriors he had each tie a tree branch to his back.

Even the warpaint with which the Senecas decorated themselves was made by Europeans.

Ganagaro was the first target. Like its sister village, Totiakton, it contained about 120 long houses, a log palisade fortress, underground storehouses and extensive cornfields. Though the Senecas had rejected one aspect of European culture, namely Christianity, they had become accustomed to European tools and weapons and grown rich plying the fur trade. From among the Indians possessions the French looted much of these European products manufactured especially for the American Indian market: cooking and hunting equipment, tomahawks and calico shirts, silver jewelry, metal hair curlers and steel springs to pluck out unwanted body hair. Even the warpaint with which the Senecas decorated themselves was made by Europeans. It was these European-made products that induced the Senecas to bring their valuable beaver mink and other pellets out of the forest. The Denonville was intent on destroying it all.

With Ganagaro in ruins, the French marched on a small Seneca village nearby, just Northwest of what is currently East Bloomfield called Gannogarae. In order to meet Seneca manpower needs, it had developed into an “adoption center” for captives from the nearly 20 tribes whose villages were situated from Alabama to Hudson Bay. While at Gannogarae, the captors were taught Seneca ways and eventually were adopted into the tribe.

The French went on to destroy Totiakton in Honeoye valley and then Gannounata, located about 2 miles north of present-day Lima. For a week they indulged in an orgy of looting, burning villages and destroying crops. The Frenchman’s Indian allies found all this work to be reprehensible. To them making war on the longhouses and corn fields that were sacred to the “Great Spirit” was an nomination, and they began to desert the French to returned to their homes.

Made uneasy by these desertions, weighted down by the sick and wounded and fearful of the Seneca counter attack, Denonville decided to lead his men back to the base at Seabreeze. He was anxious about the security of the 400 man garrison he had left there and concerned that the fort might have been overrun leaving him without boats are an avenue of retreat.

Denonville spent a restless night at Mendon Ponds, which he described as “three exceedingly pretty lakes.” The next day he brought his forces into the Seabreeze stockade greatly relieved to find everything secure. On July 26, the French set fire to their stockade and sailed westward on Lake Ontario.

Convinced he had broken the back of the Seneca power and eliminated the threat to the interests of new France, Denonville thought himself victorious. But he was mistaken. Though he had burned the Seneca corn crop, the Indians survived the winter on supplies from their Indian allies. Destroying the villages had failed to cripple them – the Senecas often abandoned settlements when the soil around them was depleted. They resettled in new villages at the southern end of Canandaigua and Seneca Lakes and continued their prospects fur trade with the Europeans.

The following summer the Senecas went on the offensive against the French, launching a retaliatory strike against Montréal. While Seneca warriors laid waste the surrounding countryside, Denonville and hundreds of besieged Frenchman cowered behind the city walls. The Senecas killed hundreds of Frenchmen and scores were burned alive within earshot of the terror-stricken citizens of Montréal. But the fighting didn’t end there. The French and English continue their struggle for control of America, while the Senecas continued to trade with both rivals, skillfully playing one off against the other. The Senecas never forgot Denonville’s raid. Seventy years later they allied themselves with the English and drove France out of North America.

Image credit « Jacques-Rene de Brisay, Marquis de Denonville » par Anonyme — Cette image est disponible au Musée McCord sous le numéro d’accès M1831Ce bandeau n’indique rien sur le statut de l’œuvre au regard du droit d’auteur. Un bandeau de droit d’auteur est requis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons –

very interesting story

Thanks Jay,

It’s especially fun if you’re a Rochesterian and know the locations.

My son and I were driving down Five Mile Line today and noticed a small historic marker titled only “Denonville Trail, 1687”. We were shocked at the date, and the subsequent obligatory google search turned up your article. He is a 10 year old homeschooler with a love of history. We had no idea this was right under our feet. Seabreeze! Ellison! Mendon Ponds! We are about to rediscover our home patch. Thank you so much.

Hi Rivka, Thanks you for taking the time to share what you two discovered. That’s pretty much how my interest began – historical marker. I remember sledding at Ellison and seeing a marker that said “Lost City of Tryon” That got me researching. And eventually I started teaching a local history 3 week elective course at Pittsford Sutherland.