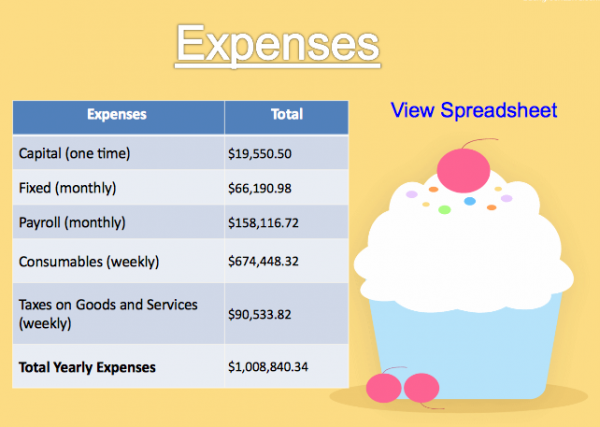

cupcake business -detail from student powerpoint

I recently blogged from the 2011 US Innovative Education Forum (IEF) sponsored by Microsoft Partners in Learning. Here’s a guest post from, Kelly Huddleston, one of the teachers I met at the competition. For more on the competition and guest posts click the IEF tag. ~ Peter

Teacher: Kelly Huddleston, Franklin Road Academy (Nashville, TN)

Project: “Create a Business”

Abstract: Working with a partner, students create a business, beginning with creating a business plan, writing a mission statement and tag line, and then creating business cards and letterhead. Students also complete a series of spreadsheets to track their income and expenses, as well as produce a commercial and design a web site. Finally, students showcase everything to the rest of the class in a Power Point presentation.

Note: This was first posted on Kelly’s blog “To Kick A Pigeon and Other Musings” For more samples of her students’ work and the rubrics she used click here.

Kelly writes:

I saw an ad on Facebook for the Microsoft Innovative Education Forum, a conference hosted by Microsoft at their headquarters in Redmond, Washington, in July. They were seeking educators who could demonstrate how they used Microsoft products in their classes in unique, innovative, and real-world ways.

Microsoft experienced the highest number of applicants ever for this conference, and I was selected for one of the 100 slots. I am also the only educator in the entire state of Tennessee attending this all-expenses paid, two day, whirl-wind conference. I am quite excited and deeply honored.

Several have asked about my submission so I thought I’d detail it here.

For lack of a better name, I simply call this project “Create a Business.” Students in my Tech class, mainly freshman, do this project each semester, and I’ve been doing it for about eight years. It continually evolves and changes, but this is where I’m at now with it.

Basically, students create a business—as much as is feasible in four months and for high school freshmen. They can work with a partner or go solo. There are many things we leave out due to time constraints such as talking about incorporating, licensing fees, legal/liability issues, creating a shopping cart for their website, etc.

My only guidelines for the types of businesses they may pursue are:

- All products/services must be legal.

- There cannot be any minimum age requirements. For example, students are allowed to sell alcohol, tobacco products, firearms, permanent tattoos, etc.

- They may not sell anything that is morally or ethically questionable even it satisfies requirements one and two.

Here’s the steps given to the students:

- Create a business plan detailing such things as the business name, products/services sold and their costs, contact information, operational hours, competition, etc. (Microsoft Word)

- Write a mission statement and tag line/slogan/motto. (Microsoft Word)

- Design a logo (Adobe Photoshop)

- Create business cards, letterhead, and other promotional print materials. (Microsoft Publisher)

- Create a series of six spreadsheets to track income, consumable inventory, capital expenses, fixed monthly expenses, payroll, and finally a net/profit loss statement for the first year with projections for the second year. (Microsoft Excel)

- Produce a :30 second commercial. (Microsoft Moviemaker)

- Create a website with a minimum of six pages: home page, about us page, contact us page, and pages to highlight all products/services sold—pictures, prices, descriptions, warranties/guarantees, return/shipping policies, customer testimonials, etc. (Adobe Dreamweaver)

- Create a presentation to showcase everything that was done to create this business. (Microsoft PowerPoint)

- Present everything to the rest of the class in a 10-15 minute presentation complete with professional business attire and bringing in “samples” of their products.

Implementation Tips

- Have a thorough grading rubric to present to students at the start of the project. I find students calculate their own grades as they go. Those who make As usually realize around the halfway point that need do some sort of extra credit to make an A. Those who don’t make the grades they desire cannot tell me they didn’t know something was required.

- Checkpoint progress throughout the process. For example, I will give my students one week to create their business cards and other Publisher documents. At the end of the week, I will check them off for a grade to make sure they are done and all basic requirements have been met. I do not grade their spelling, grammar, creativity or things of that nature at this time, although if I notice an error or design flaw, I will make suggestions.

- Show students finished examples of each new phase before they begin in. Example, before we start working on the commercial I will show my students dozens of examples of commercials the past group of students have produced. I will point out elements that were well done, creative and/or effective, and I will point out those items that could have been done better or should have done differently. I will show them A examples as well as C examples so they know what to expect going into it.

Outcomes

- Due to the nature of our school, many of my students will become owners or managers of businesses someday. I’ve actually had students so inspired by this project to start or manage their own businesses while still in high school. I’ve also had students who enjoyed and excelled at the web design part so much, they later went on to make business web sites for friends and family—for pay.

- Students are highly engaged in this project, often spending additional time outside the classroom working on it—by their choice, not because they have to. They are allowed a tremendous amount of freedom in design and creativity.

- This project prepares them for their future careers in a very authentic, real-world manner.

- I have had numerous parents each year comment to me how they wished they had a project like this when they were in school.

- I’ve had many students and parents thank me for teaching them or their children things they will actually use in the “real world.” There is no greater complement to me.

If you are interested in the details of this project for your own use in your classroom, or if you are interested in Kelly’s perspective on the Innovative Education Forum, please contact Kelly via her blog. For more about Kelly click here.