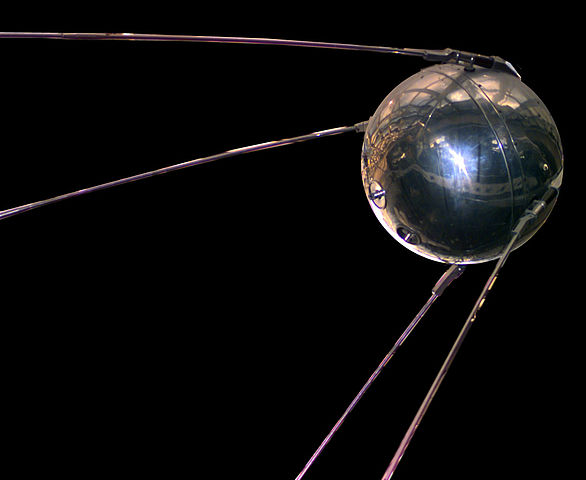

Sputnik replica

The latest results from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) are public, and already some pundits are declaring it “a Sputnik wake-up.” Others shout back that international comparisons aren’t valid. Rather than wade into that debate, I’d rather look more closely at the questions in the PISA test and what student responses tell us about American education. You can put international comparisons aside for that analysis.

Are American students able to analyze, reason and communicate their ideas effectively? [Think Common Core standards] Do they have the capacity to continue learning throughout life? Have schools been forced to sacrifice creative problem solving for “adequate yearly progress” on state tests? For more on that last question see my post “As NCLB Narrows the Curriculum, Creativity Declines.”

PISA provides some answers to those questions and offers an insight into the type of problem solving that rarely turns up American state testing. FYI: PISA is an assessment (begun in 2000) that focuses on 15-year-olds’ capabilities in reading literacy, mathematics literacy, and science literacy. PISA assesses how well prepared students are for life beyond the classroom by focusing on the application of knowledge and skills to problems with a real-life context. For more examples of PISA questions and data click here.

Do American students learn how to sequence or simply memorize sequences

Here’s one insight into what American students can (and cannot) do that can be gleaned from the 2003 PISA test results. We spend a lot of time in school getting students to learn sequential information – timelines, progressions, life cycle of a moth, steps for how to. Typically the teacher teaches the student the sequence and the student correctly identifies the sequence for teacher on the test. Thus we treat a sequence as a ordered collection of facts to be learned, not as a thinking process for students to use. This memorization reduces the student’s “mastery” of the chronology to lower order thinking. I was guilty of this when I first started teaching history “Can someone give me two causes and three results of WWII?”

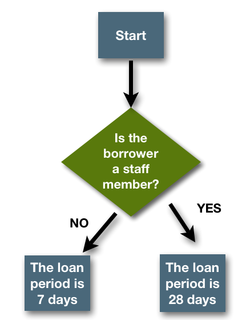

Sample sequencing problem from PISA

The Hobson High School library has a simple system for lending books: for staff members the loan period is 28 days, and for students the loan period is 7 days. The following is a decision tree diagram showing this simple system:

The Greenwood High School has a similar, but more complex library lending system: All publications classified as “Reserved” have a loan period of 2 days. For books (not including magazines) that are not on the reserved list, the loan period is 28 days for staff, and 14 days for students. For magazines that are not on the reserved list, the loan period is 7 days for everyone. Persons with any overdue items are not allowed to borrow anything.

Task

Develop a decision tree diagram for the Greenwood High School Library system so that an automated checking system can be designed to deal with book and magazine loans at the library. Your checking system should be as efficient as possible (i.e. it should have the least number of checking steps). Note that each checking step should have only two outcomes and the outcomes should be labeled appropriately (e.g. “Yes” and “No”).

Student Results

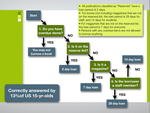

Only 13.5% of US students were able correctly answered the question. Does it really matter if students in Shanghai did any better? (The student results were rated on a rubric scale.)

When students are asked to observe a process and develop a sequence they have an opportunity to use a full spectrum of higher-order thinking skills – they must recognize patterns (analyze), determine causality (evaluate) and then decide how they would communicate what they’ve learned to others (create). Sequencing can be taught across the curriculum at a variety of grade levels – we simply have to ask the students to observe and do the thinking.

In case you’re wondering, correct response should look like this.

Click image to enlarge.