One of the best aspects of my work is that I get to meet many talented educators. I'm on the road this week, and I invited two of them to do guest posts. The first comes from Matt Karlsen, Project Director of Teaching American History Grants at ESD 112 in Vancouver, Washington. Matt and I first connected on Twitter then recently met over coffee. I was impressed with the success his group's Lesson Study approach.

There's a hysterical video called “Collaborative Planning” currently going viral. It’s a "laugh until you cry" feast, one that lays bare the hypocrisy too often evident in teacher professional development where teachers are forced into “Professional Learning Teams” that are none of the above.

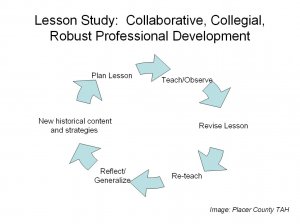

Thankfully, I’ve been able to work with teachers for the last several years using Lesson Study, a format that is collegial, educative, and transformative. In our Teaching American History grant funded project, Lesson Study starts with teachers learning new historical content. They consider state and national thinking and learning targets and examine their students’ work to get a sense of their students’ strengths and struggles. They form teams to develop a lesson trying to impact student skills and knowledge. At the same time as helping students answer questions about the historical content, they’re research lessons – helping teachers answer questions they have about teaching and learning. The group gathers to watch students interact with the lesson, spending the rest of the day discussing observations using this protocol.

Thankfully, I’ve been able to work with teachers for the last several years using Lesson Study, a format that is collegial, educative, and transformative. In our Teaching American History grant funded project, Lesson Study starts with teachers learning new historical content. They consider state and national thinking and learning targets and examine their students’ work to get a sense of their students’ strengths and struggles. They form teams to develop a lesson trying to impact student skills and knowledge. At the same time as helping students answer questions about the historical content, they’re research lessons – helping teachers answer questions they have about teaching and learning. The group gathers to watch students interact with the lesson, spending the rest of the day discussing observations using this protocol.

Why does it work?

- It’s inquiry driven. Genuine questions guide teachers and students, and the quality of the questions is continually refined to better the learning. It fosters curiosity.

- Teachers are in control. They decide the lesson targets, the questions they want students to consider and the “problems of practice” they want to investigate.

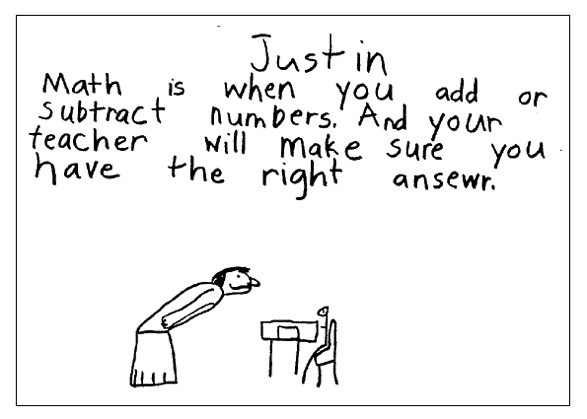

- Students are the focus. Ultimately, everything depends on what real students do with the lesson. Kid-watching eyes are developed as observations become the talking points.

- It’s flexible and adaptable. Regardless of who, what, where, or for how long you’ve been teaching, the process works.

Want to learn more?

- Catherine Lewis from Mills College has played a large role in adapting Lesson Study from Japan to the US. The Lesson Study Group at Mills College Resource Page offers links to many informative articles, videos, and books.

- Oakland Unified School District’s Teaching American History Grants have paved the way for considering Lesson Study in History. The two videos posted on their site are inspirational starting points for understanding the process.

- Feel free to contact me (Matt) to talk about Lesson Study! It was through open collaboration with others – including Catherine Lewis, Stan Pesick in Oakland, Roni Jones in Placer County, and our TAH partners – that I’ve been able to move down this path. Let’s extend the Lesson Study professional learning community!

- Two useful documents for download: 2010-11 LS Review Sheet and LS Observation & Debriefing Protocol -Fall 2010

+++++++++++++++

Interested in more teacher-friendly PD? Read my posts:

Teacher-Led Professional Development: Eleven Reasons Why You Should be Using Classroom Walk Throughs

A Guide to Designing Effective Professional Development: Essential Questions for the Successful Staff Developer

The Reflective Teacher: The Taxonomy of Reflection