Rosie the Riveter is an American icon that symbolizes the hardworking and self-sacrificing women who left the household and filled the war jobs that turned America into WWII’s “Arsenal of Democracy.” Most people’s visualization of Rosie is based on J. Howard Miller’s poster “We Can Do It!” Lacking copyright protection, it’s everywhere from history textbooks to coffee mugs. (I confess to using it for my cover below) But it’s a much bigger story than Rosie. The era is rich with public domain films, posters, pamphlets and cartoons that provide the contemporary reader with insights into the gender, race and class stereotypes of the period.

I’ve been exploring Homefront America WWII in three media-rich, multi-touch iBooks – Why We Fight, Workers Win the War, and now Recruiting Rosie: The Sales Pitch That Won a War. (All are free at iTunes.)

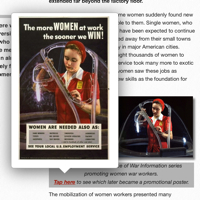

The Homefront series use WWII-era media to document the US government’s propaganda efforts. “Recruiting Rosie” focusses on how Washington’s media campaign targeted women – first coaxed them out of their homes to fill the jobs left vacant by men going off to war – then reversed course four years later to convince women to give up their factory jobs to returning servicemen and return to the roles of wife and mother in the home.

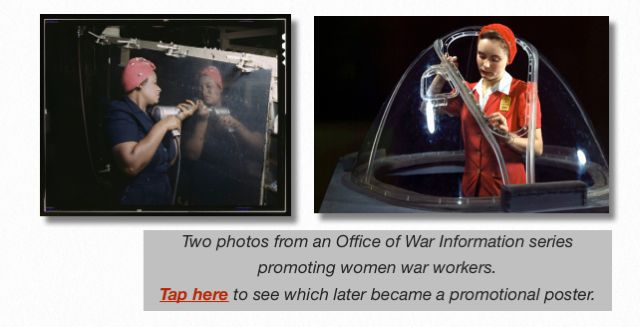

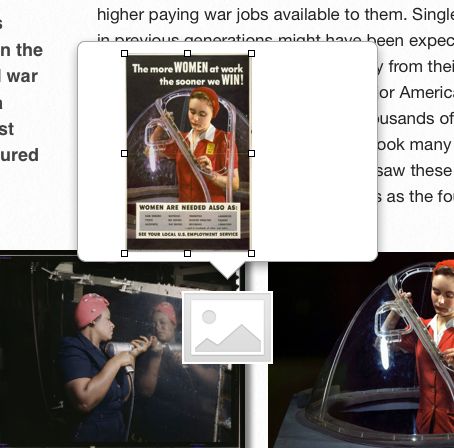

While there was great diversity in the women who did war work, the media campaign almost exclusively featured white women.

Women have always been employed in the workplace, especially minority and lower-income women. They needed little encouragement to move to higher paying war jobs. But the demand for wartime labor was so great that the US government launched a propaganda campaign to recruit previously unemployed middle class women into the workplace.

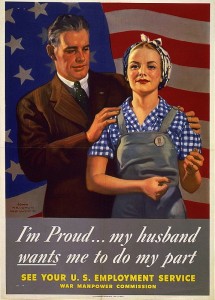

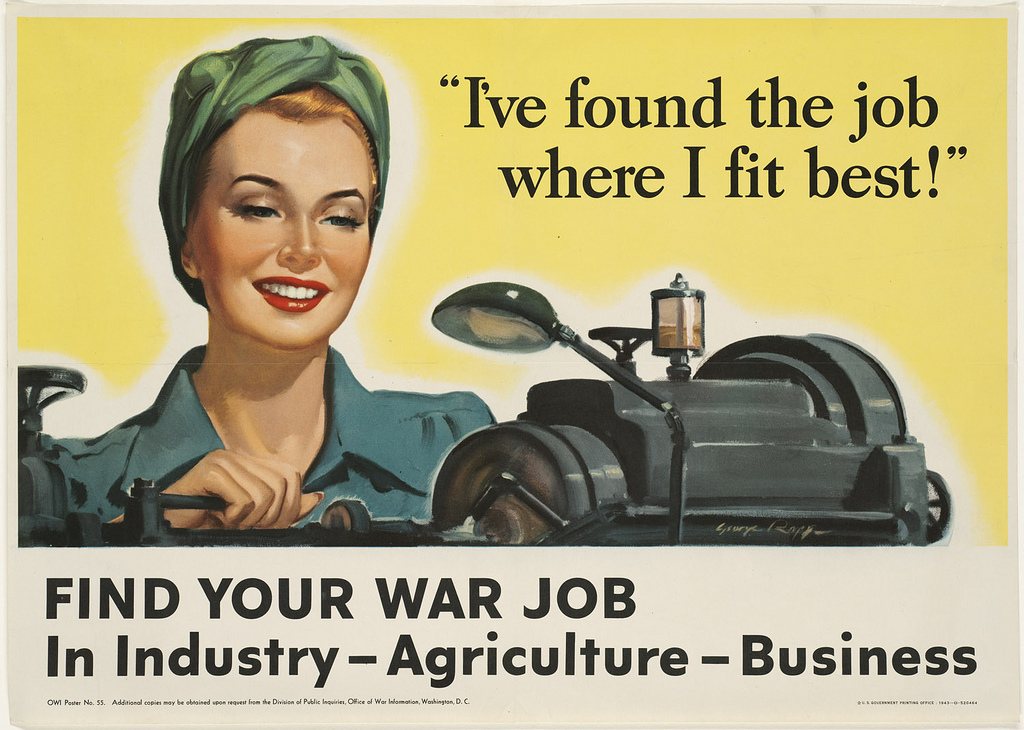

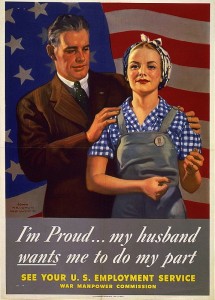

There was little reference to women working to make money – not traditionally an acceptable role for married middle class woman. Instead, propaganda was filled with themes of patriotism, sacrifice and duty that depicted war work and military service as fashionable and glamorous.

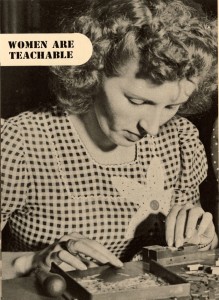

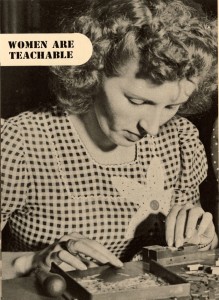

The documents in “Recruiting Rosie” explore the many facets of the campaign to mobilize women in WWII. For example, an often neglected part of the story is the extensive effort that was put into convincing factory owners and male co-workers that women could make efficient employees. As a foreman at an aircraft factory noted, “I honestly don’t believe any of us expected them [the women workers] to last the day.”

“Women scare me … at least they do in a factory.”

“Supervising Women Workers” a 1944 film designed to train plant managers opens with a male foreman telling his boss “women scare me … at least they do in a factory.” His boss replies “women are not naturally familiar with mechanical principles or machines .. you have to separate every job into simple operating steps.”

A 1943 article called “Eleven Tips on Getting More Efficiency Out of Women Employees” includes:

Tip #1. Pick young married women. They usually have more of a sense of responsibility than their unmarried sisters, they’re less likely to be flirtatious, they need the work or they wouldn’t be doing it, they still have the pep and interest to work hard and to deal with the public efficiently.

Tip #3. General experience indicates that “husky” girls — those who are just a little on the heavy side — are more even-tempered and efficient than their underweight sisters.

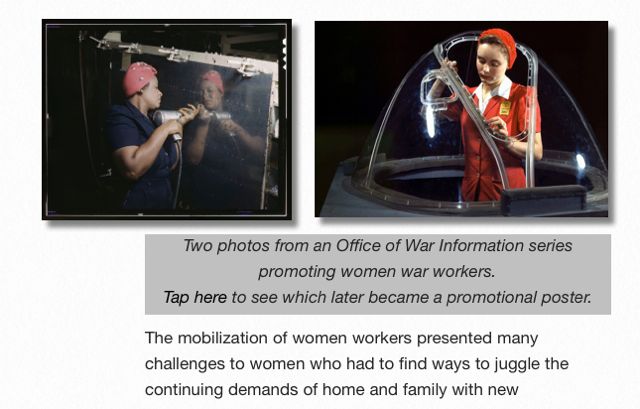

WWII-era middle class couples needed to be convinced that it was acceptable and safe for women to take jobs outside the house and work in a factory. A well-coordinated sales campaign churned out films, new stories and posters that lauded former housewives who readily mastered new industrial tasks.

Women were also needed to fill the ranks of many service jobs on the homefront, as well as enlist in the military to replace men who were being moved to the war front. The glamour of travel and the chance to meet men reoccur as dominant themes. “Its Your War Too” a recruitment film for the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) spends much of the film proving that WACs are fun, feminine, and glamorous – they get to wear makeup, choose their own hairstyles, and travel the world – always with handsome male officers as escorts.

Women were also needed to fill the ranks of many service jobs on the homefront, as well as enlist in the military to replace men who were being moved to the war front. The glamour of travel and the chance to meet men reoccur as dominant themes. “Its Your War Too” a recruitment film for the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) spends much of the film proving that WACs are fun, feminine, and glamorous – they get to wear makeup, choose their own hairstyles, and travel the world – always with handsome male officers as escorts.

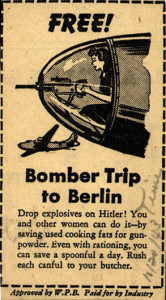

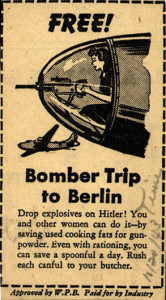

WWII required an enormous commitment of American resources and labor. Here at home, millions of families were called upon to make personal sacrifices and work harder to provide the resources needed to fight the war. Women were told to give up all luxuries and devote their energies to help win the war. “Recruiting Rosie” documents it all from asking women to volunteer on farms to a 1942 Minnie Mouse cartoon explaining how to recycle used cooking fats for armaments.

With women stretched between the demands of the workplace and home, childcare emerged as critical issue. “Recruiting Rosie” includes a section detailing the growing fears that without parental supervision, WWII would spawn a generation of juvenile delinquents. As one report noted, “Mothers in large numbers are engaged in full-time employment and are therefore absent from the home the greater part of the day. Home life is greatly changed for many children today, and lack of consistent guidance and supervision from their parents gives them opportunities for activities that may lead to unacceptable behavior.”

“How well a man fights depends a little on how well you’ve done your part in the USO and how nearly ideal an American girl you are.”

“Recruiting Rosie” features a 1943 film that depicts youngsters smoking, kids hanging out in shady bars listening to the jukebox, and young women taking up with soldiers as “Victory Girls.” “How well a man fights depends a little on how well you’ve done your part in the USO and how nearly ideal an American girl you are.” Changing sexual roles and mores of the era are explored in variety of documents from soldier-crazy “khaki-wacky” girls to a 1943 etiquette guide for teenage girls serving as junior hostesses for troops relaxing at USOs which states, “How well a man fights depends a little on how well you’ve done your part in the USO and how nearly ideal an American girl you are.”

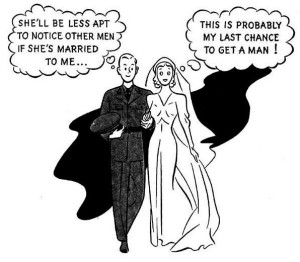

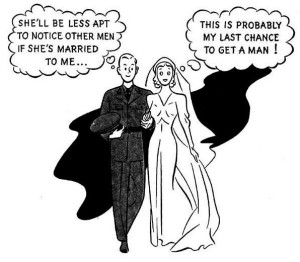

War production demanded large-scale migrations to industrial centers. With a shutdown of non-military construction, housing was limited and expensive. The wartime challenges to families are well detailed in “Recruiting Rosie.” Men and women were torn between putting marriage off or hastily “tying the knot.”

This dynamic is captured in the 1944 US War Department pamphlet “Can War Marriages be made to Work?” (illustration at left)

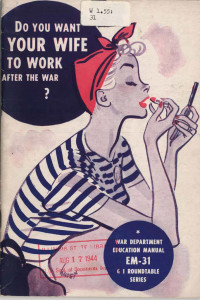

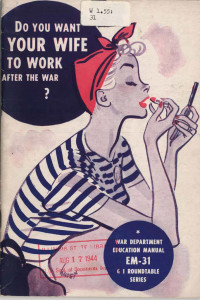

“Recruiting Rosie” concludes with the dramatic about-face as the war came to a close. The focus shifted to fears of unemployment for returning servicemen. A 1944 pamphlet entitled “Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?” opens with:

Will wives be only too glad to give up their strenuous jobs in war plants to return to the job of being homemakers? … If they must or prefer to stay at home again what will be done to make the tasks of homemaking more attractive? If a woman wants to keep on working after the war what will her husband’s attitude be? If there are no longer jobs enough for everyone should a married woman be allowed to work? Does she have as much right as her husband to try to find the work she wants?

The collection is designed to allow the student to “be the historian” as thought-provoking questions guide them through the archives while building their critical thinking / Common Core skills. The book also provides web access to the public domain content so they can remix the historic documents into their own projects.

Document analysis guides are provided in the book. “Stop and Think” prompts accompany the documents and guide student in close reading to reflect on essential questions:

- How did WWII impact women and the American family? What opportunities and challenges did the war create for women?

- How did the US government craft its propaganda campaign to shape the attitudes of women, their husbands and employers?

- How do the documents and their WWII-era depictions of women reflect the historic time period?

Like this:

Like Loading...

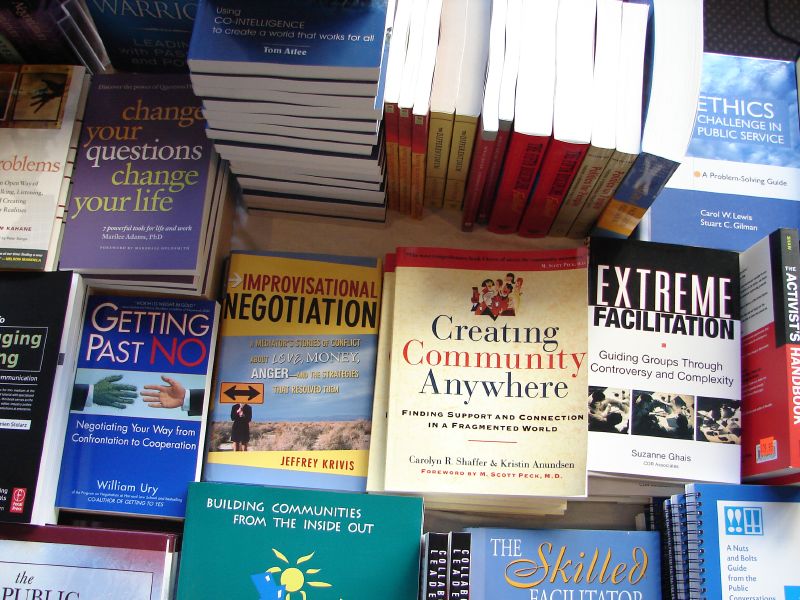

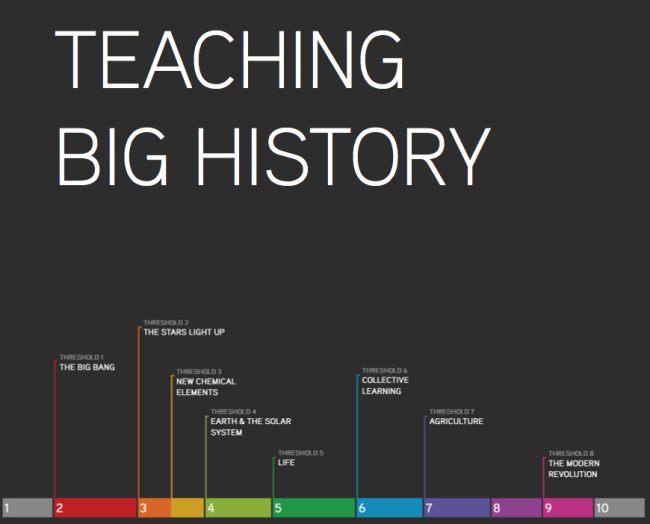

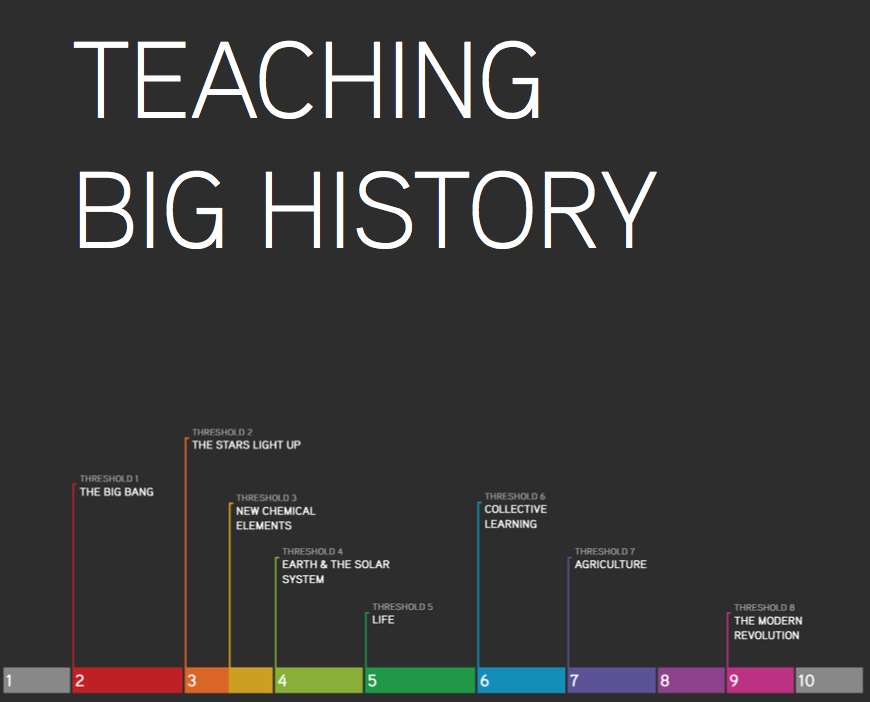

I just registered with the Big History Project – an online course that weaves scientific and historical disciplines across 13.7 billion years into a single, cohesive, science-based origin story. I always was a big picture guy. Here’s a link to the course guide and more about about the Common Core aligned program from the projects FAQ

I just registered with the Big History Project – an online course that weaves scientific and historical disciplines across 13.7 billion years into a single, cohesive, science-based origin story. I always was a big picture guy. Here’s a link to the course guide and more about about the Common Core aligned program from the projects FAQ

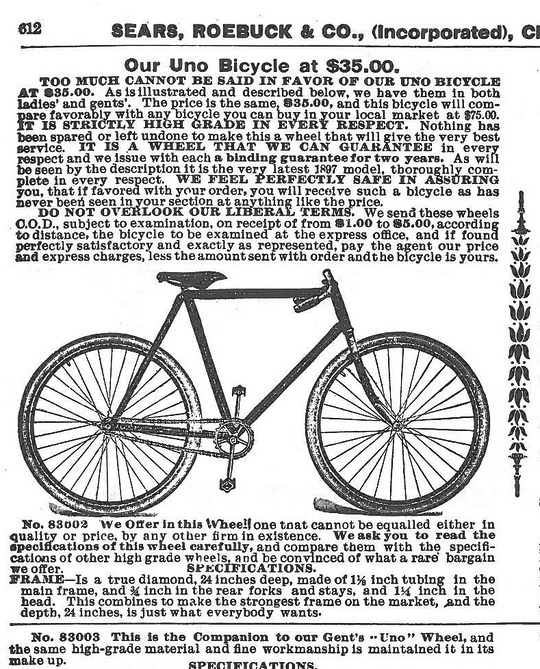

While exploring my Twitter feed I came across a very inventive 8th grade history lesson created by John Fladd ~

While exploring my Twitter feed I came across a very inventive 8th grade history lesson created by John Fladd ~

Women were also needed to fill the ranks of many service jobs on the homefront, as well as enlist in the military to replace men who were being moved to the war front. The glamour of travel and the chance to meet men reoccur as dominant themes. “Its Your War Too” a recruitment film for the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) spends much of the film proving that WACs are fun, feminine, and glamorous – they get to wear makeup, choose their own hairstyles, and travel the world – always with handsome male officers as escorts.

Women were also needed to fill the ranks of many service jobs on the homefront, as well as enlist in the military to replace men who were being moved to the war front. The glamour of travel and the chance to meet men reoccur as dominant themes. “Its Your War Too” a recruitment film for the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) spends much of the film proving that WACs are fun, feminine, and glamorous – they get to wear makeup, choose their own hairstyles, and travel the world – always with handsome male officers as escorts.