Dumas book

I recently blogged from the 2011 US Innovative Education Forum (IEF) sponsored by Microsoft Partners in Learning. Here’s a guest post from, Kelli Etheredge, one of the IEF finalists I met at the competition. For more on the competition and other guest posts click the IEF tag. ~ Peter

Kelli Etheredge, St. Paul’s Episcopal School (Mobile, AL)

Project: What’s the Verdict? The Count of Monte Cristo Murder Trial

In this project, 10th grade World Literature class students used a shared Microsoft OneNote notebook, Office Web Apps and Windows Live SkyDrive to share information and prepare for a criminal trial of the character Edmond Dantès after reading the novel The Count of Monte Cristo. Students develop many 21st century skills including critical thinking, creative problem solving, collaboration while they move beyond rote memorization and regurgitation of facts and read the book with a critical eye and goal in mind — to either prove or disprove the liability of Dantès in the downfall of his enemies and the seven deaths, two kidnappings and the loss of wealth. They gain experience in using the art of persuasion, writing in various formats and enhance civic literacy.

Kelli has written the following guest post. For a full description of the project, see her blog.

They are either reading the novel from the eye of a specific witness and discovering how Edmond Dantès impacted their lives, or they are reading from a lawyer’s perspective. They are solving the mystery, gathering evidence, looking for connections.

Intrigue. It is the key to any great story. For me, it’s also the key to any great literature lesson.

I teach World Literature to 10th graders. As with most literature curriculums, the focus is on the classics. 10th graders are generally not interested in classics. Not surprising, I know. If it wasn’t published in their lifetime, students frequently classify all classics as “boring” without every reading it. Even when they are interested in the work, nothing kills the inherent qualities of a story like the “traditional” qualities of a literature classroom. We all know the class – assign chapters to read for homework, lecture about plot and theme, repeat until done. My goal, therefore, for every unit is to bring classic literature to life. I love the day in my class when kids shift from saying, “I have to read this…” to “I get to read this!”

How do I create intrigue? For The Count of Monte Cristo unit, I use the mock trial. Now, don’t get me wrong. The Count of Monte Cristo oozes intrigue without a mock trial – love, jealousy, betrayal, vengeance. It has it all. But, with an 1844 publication date, some students may never read it without the mock trial. Therefore, when I introduce the unit, I tell the students that at the end of the novel, although Edmond Dantès never directly kills, kidnaps, or steals from anyone, we are going to put him on trial for murder, kidnapping, and theft. Intrigue. They are curious; they start reading to see how in the world such a trial can happen.

Students are then given a deadline for the first fifteen chapters and asked to tell me whether they want to be either (1) a lawyer or (2) a witness in the trial. Starting with chapter sixteen, students have a specific role. They are either reading the novel from the eye of a specific witness and discovering how Edmond Dantès impacted their lives, or they are reading from a lawyer’s perspective. They are solving the mystery, gathering evidence, looking for connections.

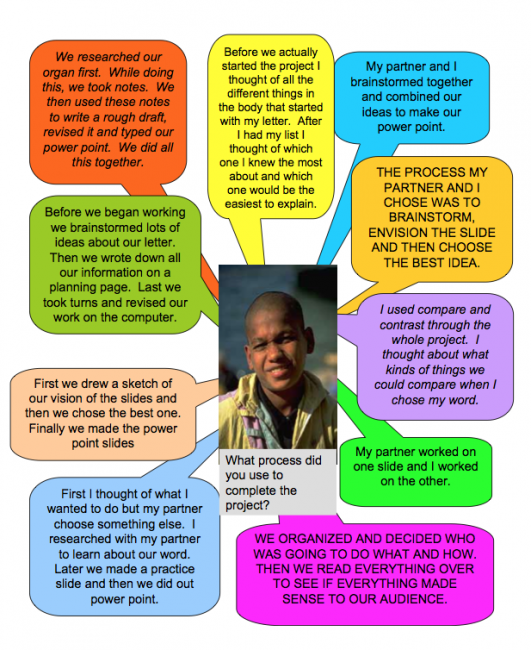

classroom mock trial

Students are given time in and out of class to read the novel. At specific chapters, the class analyzes the events in the novel and creates cause and effect charts. When the students are finished reading the novel, they then move into prosecution and defense teams to prepare for the trial. All of our work in the novel study and the trial preparation is shared via a Microsoft OneNote notebook. Prosecution and Defense teams have password protected sections. During the mock trial they can quickly search their OneNote notebook and find facts that help them respond to cross-examination remarks.

Witnesses play the part and write a letter from their character’s perspective; lawyers use an analysis chart to determine how each witness impacts their theory of the case. During the trial preparation stage, I teach the students about trial procedure, questioning witnesses, and introducing evidence at trial. When trial preparation is complete, we conduct the mock trial. Other teachers and former students sit on the jury. I’m the judge. When witnesses are not on the stand, they are taking notes to help prepare for their persuasive essay. The trial usually lasts four to five days, and we have had both defense and prosecution verdicts.

Once the trial is over, everyone writes a persuasive essay answering the question: Were the punishments of Danglars, Villefort, and Fernand Mondego really God’s retribution or wholly the cause of Edmond Dantès?

Count of Monte Cristo Preparation & Trial from Kelli Etheredge on Vimeo.

From start to finish, students are thinking critically, connecting their knowledge of the novel to their own world, and expanding their experiences. Watching each student use the facts of the case to (1) demonstrate their understanding of the novel and (2) prove their team’s case is one of the proudest moments I have every year.

Here are my tips for making a literary mock trial successful:

- Choose a novel that involves culpable activities but no one in the novel is punished for

- Assign only important roles (lawyers and characters) and assign the roles as early as you can

- Provide students with scaffolding devices that help them in their critical thinking – cause/effect charts, organization tools, analysis charts

- Make sure everyone is active during the trial; if students aren’t testifying they should be taking notes, preparing for their persuasive essay.

- Use outside experts- lawyers from your hometown- to teach students about trial procedure

- The following site has a mock trial manual (pdf) for teachers to use – (note I did not assign follow this manual completely because I wanted my students to only be witnesses and lawyers. Positions like bailiff did not provide any opportunity for critical thinking and application of their knowledge of the novel.) Additionally, this website – provides guidance on questioning witnesses, introducing evidence, etc.

- Encourage healthy competition – the students’ level of commitment to the project intensifies with a healthy competition.

- Remind students that they are capable of the task; students need to know that they are capable of hard work and critical thinking, and they need to know you have confidence in their abilities.

- Have fun!

Additional r esources from Kelli:

About the Author

Kelli Etheredge is the Teaching and Learning Resources Director for St. Paul’s Episcopal School. In her role, she supports PK-12 teachers in effective integration of technology and innovative lesson design. She is also a trained peer coaching facilitator through the PeerEd group. Additionally, Kelli teaches World Literature at the 10th grade level. She is in her twelfth year of teaching and her eleventh year of teaching in a 1:1 environment. Before her teaching career, Kelli practiced law for five years.

Image credits:

Dumas Book – flickr/jypsygen

Classroom mock trial – Kelli Etheridge

Like this:

Like Loading...