Soon I’ll be giving workshops demonstrating how to integrate literacy skills for close reading with historical thinking skills. Here’s a preview.

Soon I’ll be giving workshops demonstrating how to integrate literacy skills for close reading with historical thinking skills. Here’s a preview.

- Sept 23 – Learning Lab / EducationPlus St. Louis MO Teacher evaluations-9-23-15 244kb pdf

- Sept 26 – Oregon Writing Project ~ University of Oregon, Eugene Ore. Teacher evaluations-9-27-15 118kb pdf

- Workshop resource site: Teaching With Documents

What do we mean by historical thinking? It’s the historian’s version of critical thinking:

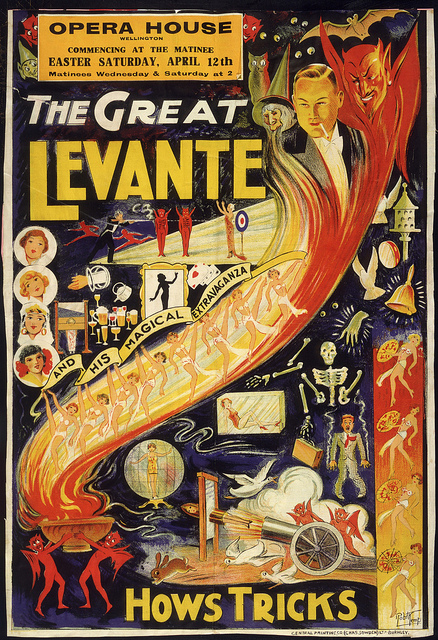

- Examine and analyze primary sources – who created it, when, for what purpose?

- Understand historical context. Compare multiple accounts and perspectives.

- Take a position and defend it with evidence.

What do we mean by close reading? Teachers can guide students with scaffolding questions that explore “texts” (in all their forms).

- Key Ideas and Details: What does the text say? Identify the key ideas. What claims does the author make? What evidence does the author use to support those claims?

- Craft and Structure: Who created the document? What’s their point of view / purpose? How did the text say it? How does it reflect its historic time period?

- Integration of Knowledge and ideas: Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text. Recognize disparities between multiple accounts. Compare text to other media / genres. How does it connect to what we’re learning? And what’s it mean to me?

Let’s look at how a close reading of historical sources for craft and structure can integrate with the historical skill of sourcing – who created it, when, for what purpose?

Here’s a great illustration of historical sourcing from Stanford History Education Group’s Beyond the Bubble.

And here’s an exercise I used with teachers at a workshop this past summer. Here’s the instructions they were given:

- Create and post a source comparison. Be sure to include: Historical question and two sample sources.

- Once other workshop members have posted their source comparison questions, use their content to answer the question: “Which do you trust more? Why?”

- Feel free to add multiple answers to the same question and / or comment on each others question / or answer. It’s a dialogue.

Here’s a Google doc with my prompts and teacher responses.

Image Source: Rogier van der Weyden, Detail from The Magdalen Reading, c. 1435–1438. National Gallery, London