My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol II. It features ten engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook version click here.

To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. More in series here.

Race hate is a reoccurring theme in wars and this DBQ gives students another avenue in which to explore it.

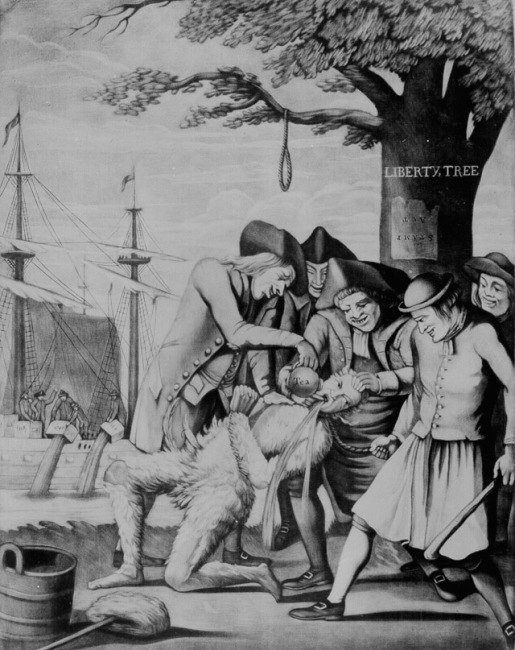

Cesspool of Savagery by Michelle Murphy Download as pdf (12.1MB) In this DBQ, students will explore the attitudes of the Anzacs towards the local population of Egypt where they trained prior to the landing at Gallipoli. Specifically, they will think about how Anzacs perceived the Egyptians and what informed their view. Racial prejudices come in many shapes and sizes and can be found in all eras. The Anzacs provide another perspective to historians. It is not my intent to belittle the bravery of the Anzacs in World War I. Rather, I want students to remember that history is not black and white. It is not simple and it is not static. It is fluid and gray. It is their job to sift through it and make a claim and support it with evidence as historians in training.

Reflection by Michelle Murphy

Thus far, the DBQ has been a very challenging, but educational experience. I initially began this journey thinking that I would do my DBQ on Operation PB Success. However, I found that would not be feasible so I changed my topic to the Anzacs in Egypt during World War I and perceptions of the ‘other.’ Through this, I have learned how to conduct a successful history lesson without a lengthy lecture. The setup of my DBQ allows students to interact successfully with the material and make an argument without needing in-depth background on the topic beforehand. Students, therefore, practice thinking like historians and the classroom becomes more student-centered.

Another lesson I have learned from the DBQ is how to find primary sources. Finding primary sources is, clearly, very important to the DBQ process. The internet makes it possible to track down hundreds of primary sources from a range of websites whether they be from an academic institutions or a small blog. In order to ensure that my sources are reliable, I have found that government websites are really helpful in locating legitimate primary sources. While it is certainly tempting to just steal primary sources without worrying about their origin, I believe it is important to ensure that I am giving my students something that is quality and genuine.

I would really enjoy using this DBQ in a class that was exploring World War I. Race hate is a reoccurring theme in wars and this DBQ gives students another avenue in which to explore it. When we think of race hate we often think of groups such as the Nazis, but it is important to show students that there are many dimensions to history and while it is easy to villains only one group, it is not necessarily accurate. Racial prejudices come in many shapes and sizes and can be found in all eras. The Anzacs provide another perspective to historians. It is not my intent to belittle the bravery of the Anzacs in World War I. Rather, I want students to remember that history is not black and white. It is not simple and it is not static. It is fluid and gray. It is their job to sift through it and make a claim and support it with evidence as historians in training.

Image credit: Coloured illustration of Anzac troops after the fighting at Gallipoli during World War I

Illustrator: Unidentified

Date: Undated

Location: Gallipoli, Turkey; 40.419071, 26.67877

Description: A New Zealand soldier stands on the left, with an Australian soldier on the right. They are holding the flags of their countries, with a Union Jack displayed above. A banner across the flags reads ‘Australian and New Zealand Army Corps’. King George V is quoted ‘The Australian and New Zealand troops have indeed proved themselves worthy sons of the Empire’.

View this image at the State Library of Queensland: hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/114320