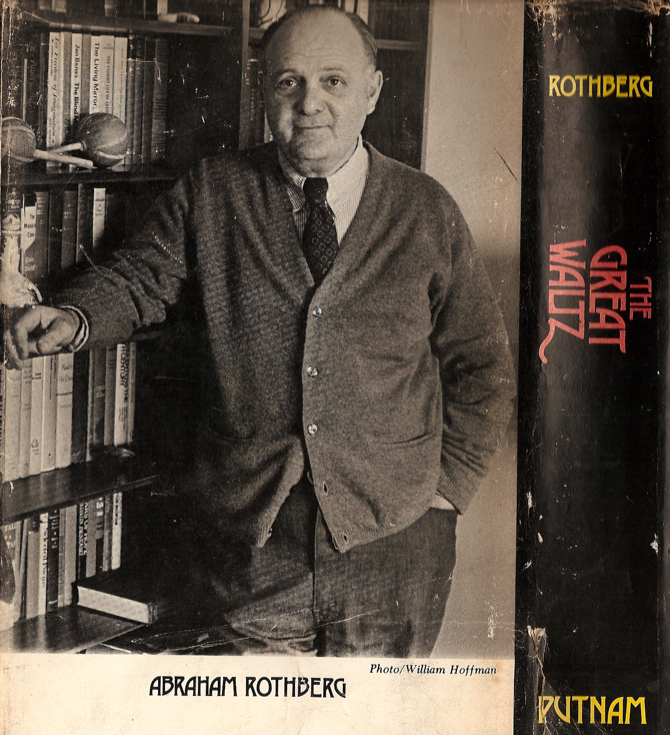

For the last 5 years I’ve been a print-on-demand publisher, producing ten books for a dear friend – Abraham Rothberg. His previous work was published by mainstream publishers and has been favorably reviewed in NY Times, Harper’s, Time Magazine, and Publishers Weekly. Unfortunately his previous work had gone out of print. So we decided to cut out the middle man and self publish.

For the last 5 years I’ve been a print-on-demand publisher, producing ten books for a dear friend – Abraham Rothberg. His previous work was published by mainstream publishers and has been favorably reviewed in NY Times, Harper’s, Time Magazine, and Publishers Weekly. Unfortunately his previous work had gone out of print. So we decided to cut out the middle man and self publish.

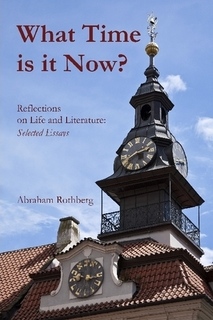

Our latest book is “What Time Is It Now? Reflection on Literature and Life.” Preview / purchase the book

The collection is a retrospective selection of essays, sharply observed and often humorous, that span almost half a century of reflections of modern life and literature, politics and personality. There is an essay analyzing the operations of British Secret Intelligence in the novels of John LeCarré, explorations of the conflicts between “superman” Social Darwinism and Socialism as portrayed in the works of Jack London. The collection contains a series of personal forays into the nature of modern marriage, of trying to “cultivate one’s own garden” in modern life, as well as how novelists have depicted the “flawed dream” of American politics. In addition, there are analyses of Gary Snyder’s poetry and their sources, Solzhenitsyn’s short stories and plays and their underlying morality, and the domestic turbulence of Arnold Wesker’s English dramas. Several essays also describe and dissect anti-Semitism in European life and literature, its roots and reverberations, and in one instance, in the works of T.S. Eliot.

In addition to five new essays, it features twenty-five previously published works including:

“The Decline and Fall of George Smiley” ~ Southwest Review, Autumn, 1981.

“Waiting for Wesker” ~ Antioch Review, Winter, 1964-65.

“Solzhenitsyn’s Short Stories” ~ Kansas Quarterly, Spring, 1967

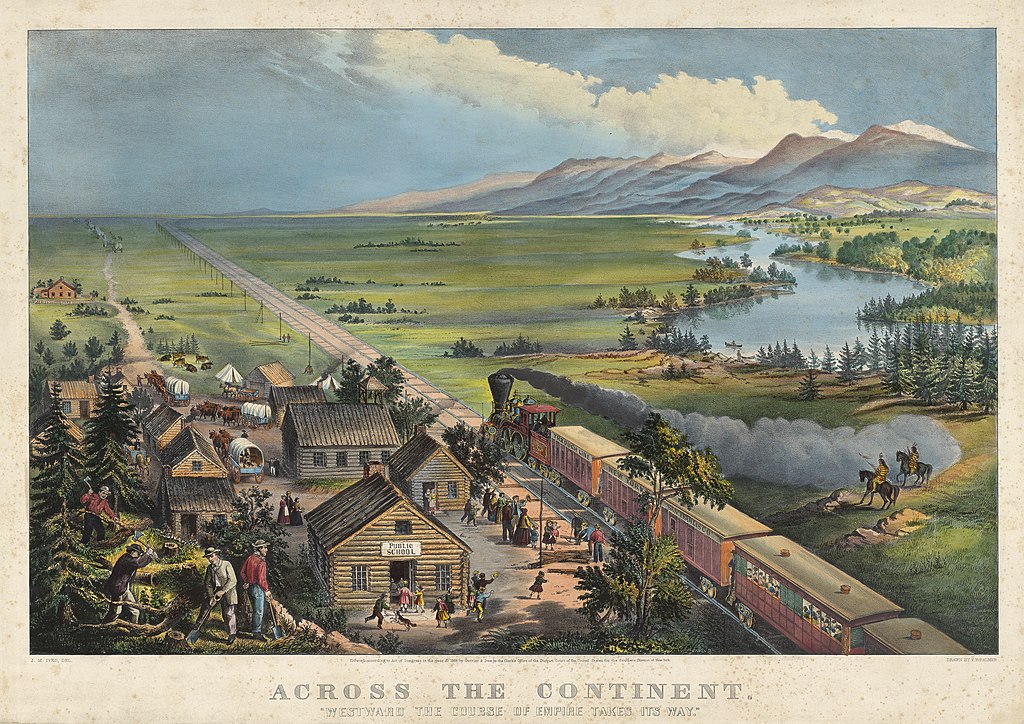

“Jack London: American Myth” ~ Bantam Books, 1963.

“The War in the Members: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” ~ Bantam Books, 1967.

“Styron’s Appointment in Sambuco” ~ New Leader, July 4-11, 1960

Read Abe’s latest reflection on his work “Fiction is a Lie that Tells the Truth“

And many thanks to my talented publishing assistant, June Tyler who designed Abe’s latest two books.