Learn and Lead

It’s always a pleasure to work with the school district that “gets it.”

Lebanon Community Schools in Lebanon, Oregon is that sort of place.

“This creates teacher leadership opportunities. It turns visits to the classroom into teacher to teacher professional development – transforming the notion of what happens when people visit your classroom.”

I was first introduced to LCS in May through their work with Oregon’s Class / Chalkboard Project. In August, I gave an opening-day faculty presentation focused on looking at learning from the students’ perspective. Since then I’ve assisted LCS in training a group of six “learning walk leaders” who will lead their peers on reflective learning walks through the classroom. As one of the leaders neatly summarized our goals, “This creates teacher leadership opportunities. It turn visits to the classroom into teacher to teacher professional development – transforming the notion of what happens when people visit your classroom.”

I have worked with many districts leading teachers and administrators on “classroom walkthroughs” (the term I generally use for the process) and conducting sessions designed to train-the-trainer. But Lebanon’s approach topped them all – their initiative with solid administrative support and a teacher-centric focus worth replicating. Ryan Noss, the district assistant superintendent attended all the training sessions, but consistently deferred to “let’s let the teachers decide how they want to do this.” Here’s how it went. (All quotes are from the six participants’ reflective journals.)

The district is supporting six teachers with stipends to lead their peers on reflective classroom walks. This week I completed three days of training with the “Learning Walk Leaders.” We first met as a whole group to discuss the opportunities and challenges of learning walks, but soon got into the classroom to try it out. Over the course of two days, I led pairs of teachers on visits to K-12 classrooms across the district. During that time, they had the chance to both experience the power of reflective discussion and see how to best focus our conversations on the students in the classroom, not the teacher.

We used a similar approach for each classroom visit. After checking with the teacher to see if it’s a good time to enter, we typically spent about 5-8 minutes in each class. While there we did not talk among ourselves or take any notes. (Visitors with clipboards make me nervous.) If appropriate, we might speak briefly with the teacher to get some background to the lesson or chat up a student who wanted to share what they were working on. But we weren’t there to try and “understand” the lesson. You can’t do that in 5 minutes. We wanted to see students in action and use that experience as a catalyst for a discussion. Think of learning walks as moving professional development from the lecture to the lab.

Think of learning walks as moving professional development from the lecture to the lab.

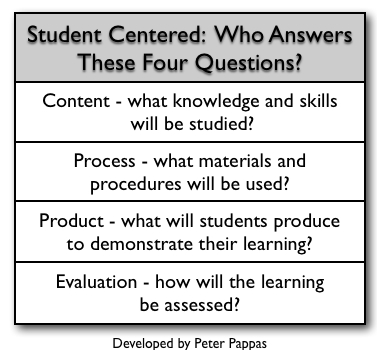

After exiting class we traveled down the hall for a brief discussion. What tasks were the students engaged in? What types of thinking did the students need to use to complete the task? What sort of choices did students need to make to complete the task? Can we find consensus about what level of Bloom’s Taxonomy best describes the student task? As Sarah Haley put it, “I love the idea of honing our reflective skills – what’s learning look like when compared to Bloom’s?” As Chrissy Shanks observed, “Learning walks gave me a fresh perspective on the ways students think.”

Often the time spent in class proved to be a jumping off point to more hypothetical discussions about student learning. “We just saw students making maps – what are the essential elements of a map? How do people use maps? What could students learn by making a real-life map for their peers to use?” Some of our best discussion about our own practice as teachers came from these extensions of what we saw in the classroom. “Teacher learning walks inspired me to become a better teacher! I learned so much about what students are doing in our district and was able to reflect on my teaching practice.” Melissa Johnson

On the third day learning walk leaders took turns “guiding” each other on visits. After each visit, they came back to central location and one leader “led” the reflective discussion in a “Fishbowl,” while the rest listened, and then offered feedback. Finally, we met to develop a protocol for how to conduct visits in the future. We want to make sure, that learning walks are seen as productive, not interruptions in the classroom. As Erica Cooper wrote “We are students of instruction in a lab setting. A trust has to be built to make it work. I want to be able to guide teachers in observing student learning to help their teaching practice.”

Next week the learning walk leaders will promote the process to their peers and begin leading reflective visits to district classrooms. We decided they needed an “elevator pitch.”

- Focus on the students (not the teacher) in a quick visit to the classroom (snapshot of learning)

- Discuss the tasks students are doing. Do we agree on what level of Bloom’s we see?

- Result – Teacher To Teacher Professional Development. Shall we call it “T3PD?”

- Best way administrators can support the effort. Ask, “Have you had interesting discussions today?” Note: don’t ask “have you seen good lessons today?” You can’t judge a lesson in 5 minutes – besides we’re watching the student.

Image credit: iStockphoto