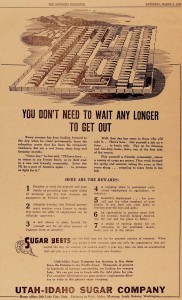

While many are aware that the US government forcibly removed and incarcerated more than 120,000 U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry during WWII. Few people know that the government recruited some of these same people to work at farm labor camps across the west to harvest crops essential to the war effort.

Uprooted from Uprooted Exhibit

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II is a traveling photography exhibit (and website) that tells this story and provides a treasure trove of resources for historians, teachers and students. Uprooted draws from images of Japanese American farm labor camps taken by Russell Lee in the summer of 1942. Lee worked as a staff photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a federal agency that between 1935 and 1944 produced approximately 175,000 black-and-white film negatives and 1,600 color photographs.

I worked with the Uprooted team and developed a lesson How reliable are documentary films as a historic source? (Lesson Plan 2) The lesson begins with the teacher telling students that they are about to watch two short videos about the experience of some Japanese Americans during World War II.

The first video was made in 2014 by documentary filmmakers to accompany the Uprooted Exhibit. It features historic video from World War II as well as oral history interviews with Japanese Americans that the filmmakers shot in 2013 and 2014. The narration is taken from the interviews.

The second video was made in 1943 by the US government as an informational service to the US public. It features video shot in 1941 and 1942 and narration by a government official. Before the videos are shown, the teacher asks the students which video they think will be a more reliable historical source. (Be sure to have them justify their thinking to their peers). Prompts include:

- A video made in the era being studied or a video made over seventy years later?

- A video made by the United States government or a video made by documentary filmmakers?

- A video narrative by a government official or a video narrated by people who participated in the event?

The lesson then guides students through comparisons of both videos based on close reading strategies – what does the video say? how does it say it? what does it mean to me?

A complete lesson plan, collection of images and historic documents is available at Uprooted. A second lesson plan considers the question: How reliable are documentary photographs as a historic source? (1.1, 1.2, 1.3) The site even includes a kit for students to curate their own Uprooted museum mini-exhibit.

You can find Uprooted on Twitter | Facebook | Flickr | Instagram

The museum exhibit open at The Four Rivers Cultural Center in Ontario, OR on September 12, 2014 and runs through December 12, 2014. It then travels to Minidoka County (ID) Historical Society and the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center in Portland Ore. More exhibit info and updates

I’d like to close this post by crediting the talented team behind Uprooted. Curator – Morgen Young, Web and Graphics Designer –Melissa Delzio, Videographers – Courtney Hermann and Kerribeth Elliott. Uprooted is a project of the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission.

Image credit: Child waiting to be taken to Manzanar, April 1942, Los Angeles, California. Photographer Russell Lee. Library of Congress (Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, LC-USF33-013290-M4)

Two children in camp c. 1943 Minidoka concentration camp Idaho

Two children in camp c. 1943 Minidoka concentration camp Idaho