My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol II. It features ten engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook version click here.

To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. More in series here.

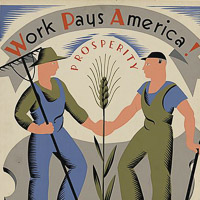

Essential Question: How did the WPA use art to influence public opinion?

The New Deal and the Art of Public Persuasion

by Kari VanKommer Download as pdf (6.6MB)

The Federal Arts Program or the FAP was one arm of the WPA solely dedicated to the creation and promotion of the arts in America. One of it’s major undertakings were the creation of promotional posters, today known as the WPA Poster Collection. Between the years 1935 and 1943, the WAP and FAB collectively created and printed more than 2 million posters on more than 35,000 unique subject matters.

There are several key techniques academics used when analyzing materials that is created to persuade and in this DBQ these techniques will be helpful to use as well. The most import questions to ask yourself when looking at all of the posters in this collection are below.

- What is the ideology and purpose of the propaganda?

- What is the context in which the propaganda occurs?

- Who is the propagandist?

- What is the structure of the propaganda organization?

- Who is the target audience?

- What techniques for persuasion are being used?

- What audience reactions are the techniques hoping to elicit?

Reflection by Kari VanKommer Twitter/@MissKVK

This project was such a great opportunity to try my hand at creating the type of relevant history lesson that I want to include in my curriculum as a future social studies teacher. Unfortunately, I did not fully take advantage of it as I wish I had. Initially I struggled narrowing down a subject, I wanted to land on something I felt a strong personal connection to which would also be relatively simple to construct a DBQ project around. Quickly settling on the topic of communism and the Red Scare, I felt confident, perhaps a little too confident. When I realized that someone had focused on that topic last year for this project, I decided that topic would no longer work for me. I could have carried on with the communist angle and perhaps focused more specifically on one aspect of it such as the Rosenbergs or the Cuban Missile Crisis, but my internal drive to be as close to original as possible forbid me from this. Instead I decided to switch gears entirely.

After debating various topics in my head from Civil War Reconstruction to the often forgotten historical figure of Noah Webster, of that dictionary we refer to from time to time (who I discovered in my preliminary research may have been a thoroughly unlikable fellow which is why his contributions to the founding of the USA have largely been forgotten…) but I digress. After bouncing around a variety of ideas after the Red Scare topic fell through, I finally settled on focusing my DBQ on the New Deal and the various forms of propaganda and art that came out of that time period in American life.

This period in history is complicated and filled with difficulties and political initiatives that mirror our own times to such a degree it is almost unsettling. Much as President Obama has needed to sell his ideas for recovery and change in the last six years such as the Affordable Care Act, so FDR needed to sell his plan for getting America out of the Great Depression. The poster collection created by the WPA and FAP between 1933-1943 is one of the first things I re-discovered when researching this topic. They are beautiful, modern and striking. The have an agenda, often times more than one and they have much to tell us about what art can do to shift public opinion, and what those responsible for creating those posters believed needed to be shifting.

Once I settled on a topic my drudgery through this project was not alleviated. I did not have a focused point of view or purpose for the posters though I know I wanted to use them. Peter Pappas helped me collate my thoughts on what things could be asked of students in relation to the artwork and what conclusions or inferences could be drawn that might be helpful. My resulting DBQ project is not the best thing I have every produced, but it is definitely a place to start. As one of my favorite authors Elizabeth Gilbert has said “You must be very polite with yourself when you are leaning something new.”

If I could do it again I would get started much sooner, put my head down and find a topic I felt was original and interesting. I might have focused on maps or the layout of cities in America or something closely related to that. The good news is I hope to be at this for a while and I think the benefit of DBQ questions can not be understated, so I might just get me do-over shot after all. For now it’s about doing the best you can and learning that procrastination does not a stellar project make.

Image credit: Work pays America! Prosperity.

Library of Congress: LC-DIG-ds-04632