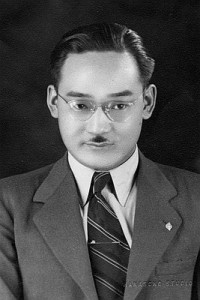

On the evening of March 28, 1942, Minoru “Min” Yasui, deliberately violated the racially discriminatory curfew against Japanese Americans to test its constitutionality, walking on NW 3rd Avenue in downtown Portland. Min’s lifelong fight for justice and equality led to his recognition as the first Oregonian to be awarded (posthumously) the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

On the evening of March 28, 1942, Minoru “Min” Yasui, deliberately violated the racially discriminatory curfew against Japanese Americans to test its constitutionality, walking on NW 3rd Avenue in downtown Portland. Min’s lifelong fight for justice and equality led to his recognition as the first Oregonian to be awarded (posthumously) the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

At the age of twenty-six, Yasui put his professional career and his personal liberty on the line for justice. He spent 9 months in solitary confinement at the Multnomah County Jail as he appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. He was released from jail in 1943, only to be sent to the Minidoka American concentration camp in Idaho. More

Join us to retrace Min’s historic walk for social justice on March 28th

Please join us on Monday, March 28, as we retrace Min’s historic walk from his law office in the Foster Hotel in Old Town, to the former site of Police Headquarters on SW 2nd Avenue and Oak Street. Gather at Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center (121 NW 2nd Avenue Portland Ore 97209 map) at 4:30 pm for the short 6 block walk followed by a program in the foyer and reception in the offices of Stoll Berne at SW Second Avenue and Oak Street. Download flyer 389KB pdf

Yasui was awarded the 2015 Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the country. The Oregon Senate and House unanimously recently passed a historic bill designating March 28 of each year as Minoru Yasui Day. More from the Min Yasui Tribute Project

Never Give Up! – Trailer from Minoru Yasui Film on Vimeo.

Minoru Yasui was born 100 years ago in 1916 in Hood River, Oregon, son of Japanese immigrant parents. He was the first Japanese American to graduate from the University of Oregon School of Law, and the first Japanese American member of the Oregon State Bar.

After the war, he moved to Denver, Colorado, where he continued to fight for human and civil rights of all people. In the 1970s-80s, he spearheaded the national movement for redress: an official apology and reparations for Japanese Americans imprisoned in the World War II camps.

In 1983, he returned to Portland to reopen his wartime case in the U.S. District Court of Oregon. While his conviction was vacated, the court denied his request for an evidentiary hearing, which he appealed. His case was pending in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals when he died in 1986. Minoru Yasui is buried in his beloved hometown of Hood River, Oregon.

Image credit: Holly Yasui / Oregon Encyclopedia link

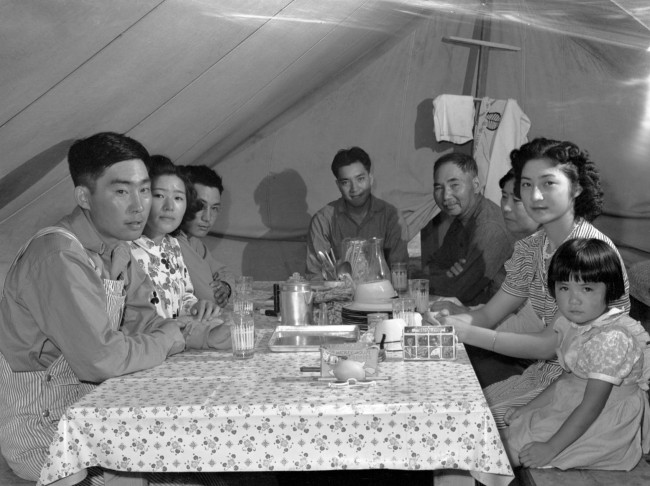

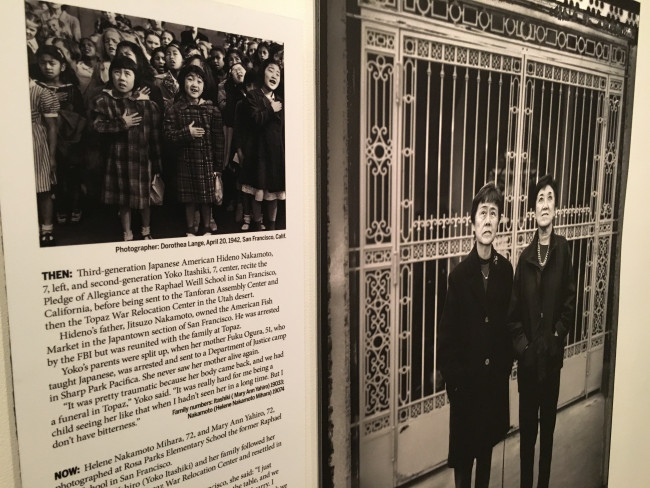

Pledge of Allegiance: Hideno Nakamoto and Yoko Itashiki at age 7 and at 72

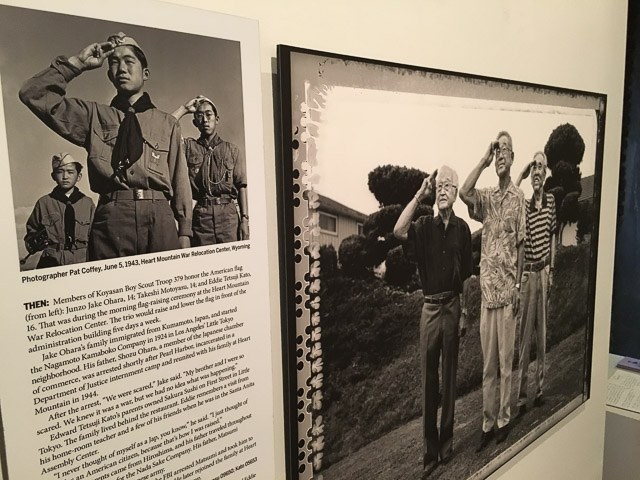

Pledge of Allegiance: Hideno Nakamoto and Yoko Itashiki at age 7 and at 72 Incarcerated at Heart Mountain: Three Boy Scouts Honor the American Flag (1943 and today)

Incarcerated at Heart Mountain: Three Boy Scouts Honor the American Flag (1943 and today)