I’m pleased to served as an advisor to a new interactive resource for teachers and students. “Picturing the Story: Narrative Arts and the Stories They Tell” uses world art from the permanent collection of the Memorial Art Gallery dating from 1500 BCE to the 20th Century. Each work has a story to tell, either visually through imagery and symbol, or indirectly through custom and ritual. The stories reflect sacred beliefs, folk traditions, common human experiences, or unique cultural practices.

I’m pleased to served as an advisor to a new interactive resource for teachers and students. “Picturing the Story: Narrative Arts and the Stories They Tell” uses world art from the permanent collection of the Memorial Art Gallery dating from 1500 BCE to the 20th Century. Each work has a story to tell, either visually through imagery and symbol, or indirectly through custom and ritual. The stories reflect sacred beliefs, folk traditions, common human experiences, or unique cultural practices.

Each work of art includes downloadable resources – the story that inspired it, the culture where it originated, the techniques used to produce it, as well as extensive lesson plans, activity suggestions, and recommendations for further reading. The lessons and stories are designed to be used at a variety of grade levels.

Downloads resources include:

- Classroom Copy – Printable, condensed version of online materials, copy-ready for classroom use.

- Curriculum Connections – Organized by subject area: Social Studies, ELA, Science, Art/Art History. Lesson extensions, children’s book recommendations, and activity suggestions, most with accompanying activity sheets.

- Learning Skill-based Activity Sheets: Printable, copy-ready sheets that address specific learning skills, for classroom use with online materials or printed classroom copy. Includes skills such as constructing comparison, identifying context, recognizing sequence and many more.

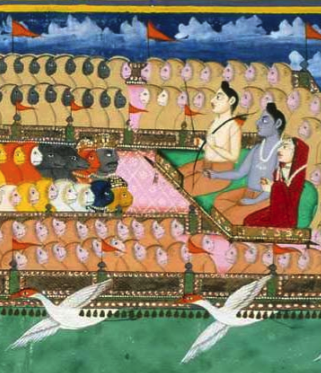

Every work of art has a story to tell. These stories can explain the unexplainable, teach a life lesson, or celebrate our common human experiences. Each work in this collection is approached from three different perspectives:

Every work of art has a story to tell. These stories can explain the unexplainable, teach a life lesson, or celebrate our common human experiences. Each work in this collection is approached from three different perspectives:

1. Picturing the Story: Viewing a work of art while reading/hearing/seeing its associated story. The story is available as on-screen text, as an audio file voiced by a professional storyteller, in ASL video interpretation, or printable pdf version. In addition, an audio “guided-looking tour” of the work of art by a museum educator helps focus attention on important details and promote visual and verbal looking skills.

2. Reading the Art: Understanding the symbolism and references used in this work of narrative art. High-quality images of works of art, with zoom-able details, comparison or supporting images, and interpretive information connect elements of the work of art to its associated story.

3. Connecting the Culture: Exploring the cultural and functional context of this work of art. Historical and cultural context information, including maps, supporting photos, and other images, connect the work of art and the story to the cultural background, promoting document-based and inquiry-based learning. Information addressing purpose or function of work, biographical information on artist (as available), geographical and environmental issues, and process and tools of creation allows the objects’ significance to extend into a variety of curriculum areas.

Details from:

“The Fox and the Heron” Flemish, Frans Snyders ca. 1630-1640

“Rama, Sita and Lakshmana Return to Ayodhya” Indian, Rajasthan, Rajput School ca. 1850-1900