My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Sixth of 13)

My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Sixth of 13)

The Lynching of Leo Frank by Jeff Smith

Download at 3MB pdf

My great-grandfather, William Smith, was one of the lawyers involved in the trial of Leo Frank.

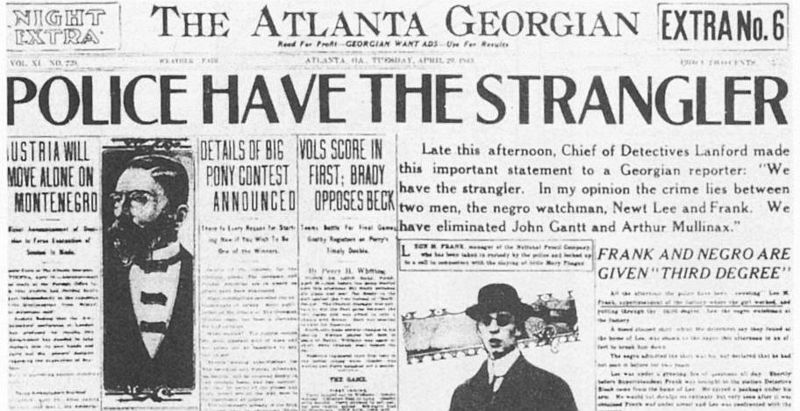

In the early morning of April 27th, 1913, the body of Mary Phagan was found strangled to death in the basement of an Atlanta, GA pencil factory. Next to her body the police discovered two semiliterate notes that seemed at first to have been written by her (“i wright while play with me,” read one) but were plainly the work of someone else.

The investigation focused on two suspects: Jim Conley, the factory’s black janitor who was arrested after he was seen washing out a bloody shirt a few days after the murder, and Leo M. Frank, the factory’s Jewish supervisor and the last man to admit to seeing Mary Phagan alive.

After intensive interrogation, Conley claimed Frank committed the murder when the girl rejected his sexual advances. Conley added that Frank dictated the notes to him in an effort to pin the crime on another black employee.

Frank and Conley were both arrested, and the ensuing trial captivated the entire city of Atlanta. The case also brought to the forefront the ugly realities of bigotry, prejudice, and hatred in the South.

Reflection by Jeff Smith

As I began thinking of topics for our document-based lessons, my mind immediately went to a topic with a strong family connection. My great-grandfather, William Smith, was one of the lawyers involved in the trial of Leo Frank. (representing Jim Conley).

However, this dark chapter in the history of Atlanta, Georgia and the Jim Crow South is heavy material, dealing with racism, bigotry, prejudice and lynching. All are certainly important issues worthy of a lesson, but the incident is not the most light-hearted affair. I thought I might prefer to investigate in-depth a more approachable topic, but my family ties made the subject too attractive to ignore.

I was indeed correct in the difficulty of the material, and, as I dug deeper, ugliness after ugliness bubbled to the surface. The topic also began to touch on a broad range of issues in the South, and focusing my lesson on specific documents and skills became an problem. I decided to focus on media coverage of the event, comparing the coverage of competing local papers and the unseemly journalism that was practiced.

The most frustrating part of my research experience stemmed from the controversial nature of the topic. As I google-searched various people and incidents, I noticed odd websites popping up. I learned a bit more about these websites, and apparently the lynching of Leo Frank continues to be a linchpin topic for hate groups to this day. There are several phony educational sites, published by hate groups, detailing “evidence” of Frank’s guilt and the conspiracies working to have him pardoned. Unfortunately, these sites seemed to have hi-definition copies of famous photographs from the case, and it proved difficult sifting through the fake sights to obtain quality documents from reputable sources.

Overall, I felt the iBooks DBQ project was the most meaningful piece of work I produced in the MAT program this semester. Not only did I learn more about my own family’s history, but I also obtained a useful new tech skill.

In fact, in my spring placement I’ve decided to have my students use iBooks author to do a project of their own, presenting a story from a revolutionary period in the form of a children’s book. The kids will create iBook chapters, assemble them into a collection, and present their stories to an elementary school class. Their work will then be made available for the whole school to peruse, and for next year’s 7th graders to refer to when making their own book.

Image credit: Wikimedia: The Atlanta Georgian, April 29, 1913