I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column Teaching History By Encouraging Curiosity Note: you can also listen to our 10 minute podcast on the subject at BAM radio or iTunes

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column Teaching History By Encouraging Curiosity Note: you can also listen to our 10 minute podcast on the subject at BAM radio or iTunes

The column prompt was “What are some stories (testimonials) of the process teachers experienced when moving from the ‘stereotypical history teacher who only gives multiple choice tests on the dates of battles and offers their students a steady diet of mind dumbing worksheets and lectures.’”

I thought I cross post my response below for readers who do not have access to content behind the Ed Week paywall.

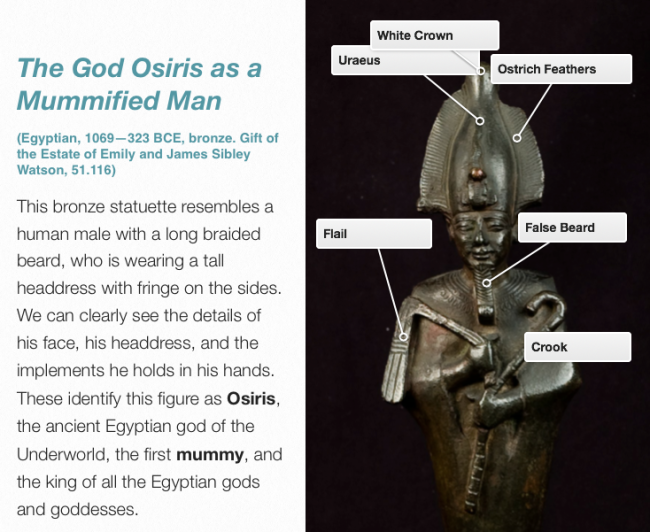

What do historians do? Research, interpret, and evaluate sources, apply historic perspective, pose questions. … they share the fruits of their research with others, take positions and defend them.

Let me share my evolution as history teacher. In 1971, I began teaching history much the same way it was taught to me. I did all the reading and assimilation of material, then worked hard to craft the interesting lecture. I delivered the information with great gusto and loads of clever asides. Then I gave the objective unit test to see if the students got it. I was doing all the work; learning far more than my students; preparing and delivering “five shows daily.” And so I trudged through history – Plato to NATO.

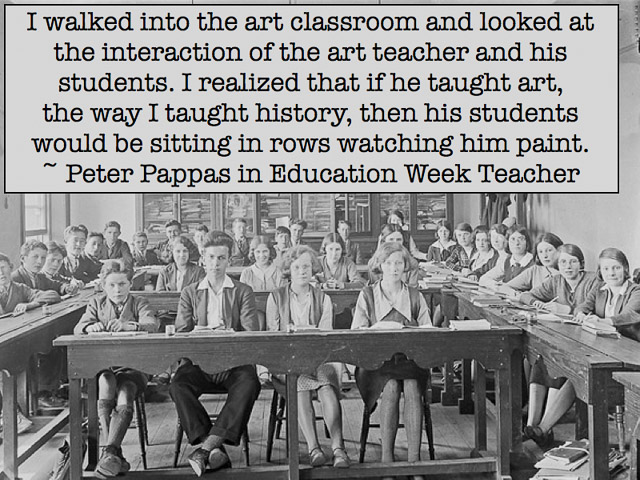

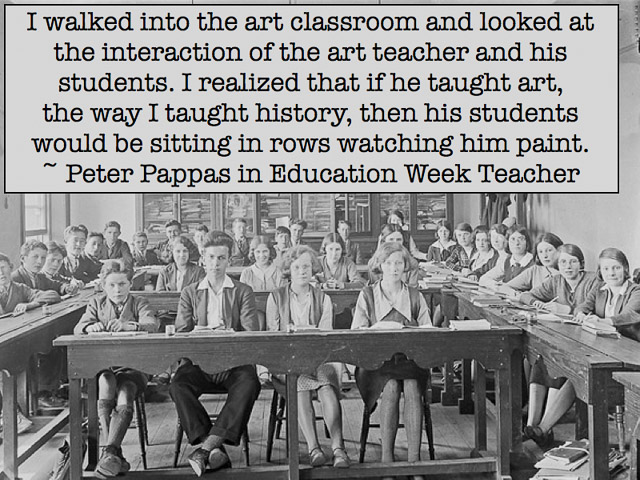

Then one day I had a revelation. I walked into the art classroom next door to borrow some supplies and looked at the interaction of the art teacher and his students. I realized that if Tom taught art the way I taught history, then his student would be sitting in rows watching him paint. And so my journey began. Just as Tom was teaching his students how to think and behave like artists, I needed to figure out how to get my students to be the historian.

Here’s a few key ideas I considered when making the transition to student as historian. Note: For more, see my Slideshare The Student as Historian

Teach how historians think and behave:

What do historians do? Research, interpret, and evaluate sources, apply historic perspective, pose questions. More importantly they share the fruits of their research with others, take positions and defend them. Make these skills the basis of your class and you’re on your way to meeting Common Core standards. Build in opportunities for students to peer review each other’s work and reflect on their progress as learners. See my Taxonomy of Reflection for prompts.

Stop teaching facts and let students explore essential questions:

Look at a contemporary issue in the news and use it as catalyst for understanding its historic roots. Why teach the Federalist vs. Anti-Federalists debates? Better to frame the lesson around the essential question “How Powerful Should the National Government Be?” It’s timeless and extends the issues raised by the rise of the Tea Party back to the debate over the ratification of the constitution. Download my free Great Debates in American History

Use history as a platform for teaching across the curriculum:

Why not teach some graphing skills using historic census data? A great chance to design an infographic. Historians rely on key literacy skills like summarizing and comparing. Frame tasks for the students that allow them to develop their own summaries and comparisons, share them with their peers and defend their thinking. Those are more Common Core skills.

Choose the right primary and secondary sources for students to work with:

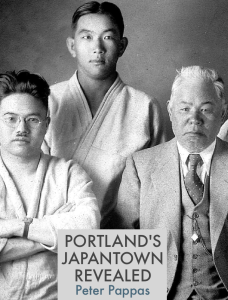

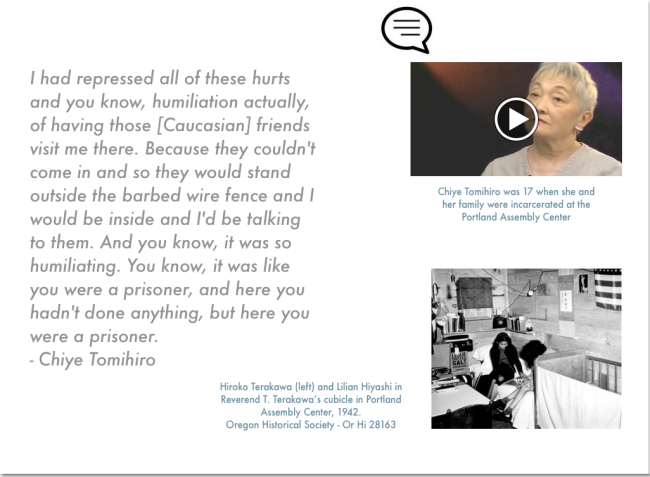

Visualize the famous “Golden Spike” photo taken to mark the completion of a transcontinental railroad line in 1869. What can a student learn by looking at the image? Not much, because the important information is not in the image. It’s in the background knowledge a student must already possess to interpret it. Unfortunately, this type of photograph dominates our textbooks. It’s iconic – it refers to something else that we want students to know. More

Instead use historic sources that are less reliant on background knowledge. Allow students to make their own judgments about source material and share what’s important to them (instead of just repeating the details the teacher highlights). It’s a great chance for them to put those summarizing and comparison skills to use.

If you have access to Ed Week, I urge you to read the article. It also features a great response from Diana Laufenberg, who notes:

Now, I’ve never had a class start with, “Miss… I just have to know about the War of 1812, can you please tell me more?” The majority of students don’t come to class naturally curious about the stories of history. However, when you take the time to pull the students from their own experiences, allow them to make connections to history, float back to modern day to again find further connections and go back into history with all that information – meaning starts to develop in a way that is not achieved otherwise.

And interesting interesting observations from Sarah Kirby-Gonzalez, including

When I first stepped away from the basic, bubble-assessment curriculum and into a more inquiry-based approach, I was surprised by my students’ reactions. I had assumed the students would eat up the rich lessons, yet their first reaction was one of discomfort. When my good, little memorizers didn’t easily earn a perfect score on an assessment, they were frustrated and shut down. After much reflecting, I realized they were out of their comfort zone and not used to being asked to think critically. Answers didn’t come easily, and since often their self-image of being smart is wrapped up with things coming easily, the students felt attacked. Slowly, the students began to thrive and rise to the challenge.

Here’s some interesting comments from Part II of Larry’s series Teaching History By Not Giving ‘The Answers’

First from Bruce Lesh, who writes:

Colleagues looked at me funny as students began to ask questions and engage in debates about historical evidence. My peers–who have been trained (as I was) to lecture, assign readings from the books, break things up with Hollywood movies, and test with quickly graded multiple-choice questions–wondered why I was challenging “what has always worked.”

…Students had become accustomed to history being taught in a certain manner. In their effort to learn to “do school,” they expected to come into the history classroom and be regaled with stories of the past distributed through lectures, films, and textbooks, and they had mastered the skill set necessary to “do history.”

And this response from PJ Caposey, who notes:

When working with teachers I focus on … trying to change from the ‘status quo’ to what is best for kids. One [element is the] Google test. If it can be answered via a simple Google search – then very little instructional time should be spent on it and it should not be assessed. CCSS is a game-changer, so too can be the ‘Google Test.’

Image credit: Flickr / Classroom scene, [Strabane technical school, Northern Ireland]

Date: c.1930

Like this:

Like Loading...

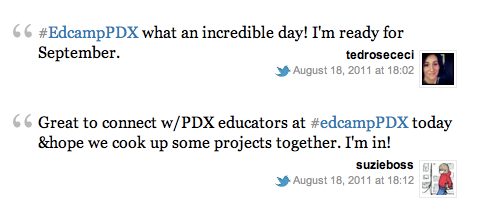

On behalf of our local team of organizers, I’m pleased to welcome you to our 10th edcampPDX since 2011. It’s time to get pumped up for the new school year- network and share new ideas with your colleagues.

On behalf of our local team of organizers, I’m pleased to welcome you to our 10th edcampPDX since 2011. It’s time to get pumped up for the new school year- network and share new ideas with your colleagues.

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column

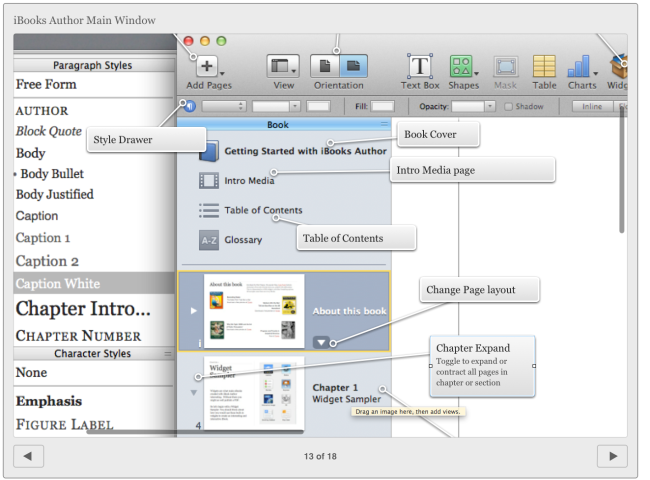

Here’s session one of my recent iBooks Author (iBA) training workshop. This one-hour session was designed to introduce iBA to about a dozen teacher at

Here’s session one of my recent iBooks Author (iBA) training workshop. This one-hour session was designed to introduce iBA to about a dozen teacher at