My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (last of 13)

My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (last of 13)

Battle of the Somme by John Hunt

Download as PDF 768 KB

What are the different ways we can construct a narrative of this battle from the perspectives of these unique players?

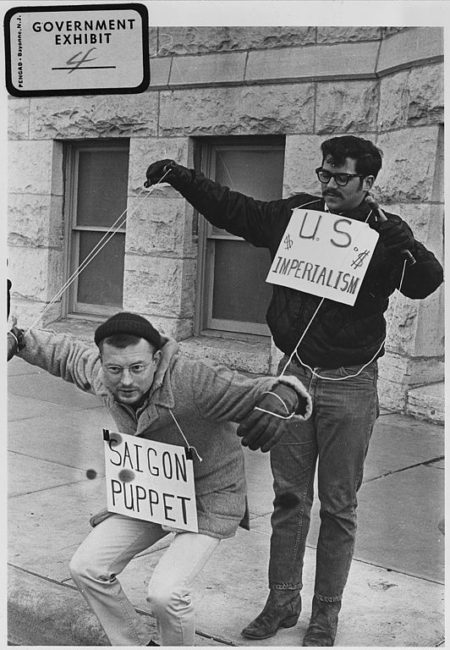

The Battle of the Somme, or the Somme offensive, was the first major British offensive of WWI. It was also the most bloody, resulting in more than 57,000 British casualties in the first day. This outstripped the total number of casualties the British suffered during the Korean, Crimean, and Boer war combined. These staggering losses occurred, in part, due to a faulty strategy. The joint British-Franco force relied upon an artillery barrage that lasted several days in order to weaken the German line. However, due to the heavily entrenched position of the Germans, the artillery proved largely ineffective. When it came time to order the charge, the British command was so sure the Germans had been decimated, they ordered their men to walk – in orderly lines – across No Man’s Land. The result was pure devastation as the unscathed Germans opened up with the automatic fire of their machine guns and mowed down men line by line

Reflection by John Hunt

The creation of an iBook is fundamentally different from anything I have ever done before. It is a truly strange creature, halfway between the old publishing world and the new world of digital media. This is true in more ways than one. Not only does the power of publication, and dissemination, lie in one’s own hands, the inclusion of digital media upends the traditional book format. Videos, pictures, and interactive widgets replace text. The author becomes more than a writer. Rather, they take on the role of designer and publisher as well. It is truly a democratization of the publishing process, even more so than previous online publishing platforms.

More than all of this though, it is a unique way to present history. We all know that history is dry. Although we might imagine science or even math using interactives, history has a special place in the realm of books. It is something we have always read. Part of history’s mythos, its identity as a scholarly pursuit, is sitting down with a dusty tome and discovering facts line by line. That is no longer the case. There is nothing particularly more or less intellectual or factual about reading. People listen, people appreciate art, and people watch movies. These are all valid sources of information and deserve the place in history afforded by platforms such as the book.

Despite this, the actual creation of my chapter – a reflection on the different experiences during the Battle of Somme – was fraught with a return to tradition. I am very used to writing. In middle school, I made longer and more complex sentences just to get a higher Flesch-Kinkaid grading level. Although I have come a long way since then, it is still the medium I am most comfortable communicating with. The comments I received on the rough draft of my chapter reflected this. They all revolved around the same themes: less text, break things into chunks, make the questions easier, and more. Obviously, I will have some difficulty thinking of a book as more than just a medium for words.

Even so, I was very happy with the eventual outcome of my chapter. It is minimal. There are no fancy widgets, less pictures, and more text. Yet I believe I have struck a good balance. It is a balance between the old and the new, the traditional format and the possibilities of a digital one. However, it is also a balance between two more simple concepts. Words still have a fundamental ability to communicate the human experience like no other medium. To close, let me reflect on the quintessential saying a picture is worth a thousand words. Although the basic premise holds true, it is far from being the case in all instances. In today’s media saturated social spheres, the power of the image is incredibly diminished. We are used to images representing the shallow, crass demands of a consumer marketplace that demands our constant attention. In this new world, the power of words to speak to our innermost emotions, remains un-belied – and perhaps even more powerful.

Image credit: Scene of British troops advancing, staged for the film “”The Battle of the Somme” Wikipedia

Like this:

Like Loading...