Close reading (in the Common Core) requires students to consider text (in it’s different forms) through three lenses: what does it say, how does it say it, and what does it mean to me? Summarizing is an essential skill for learning, but too often in school we simply ask students to “guess” what the teacher (or author) thinks is important.

An essential part of a summary is that it needs to be expressed to an audience. In life, we purposefully craft summaries for a specific audience (directions for the out-of-towner, computer how-to for the technophobe). In school, the tacit audience for most summaries is the teacher. Imagine how a student feels when asked to summarize a textbook passage for the teacher. In effect they have been asked to summarize one expert’s writing for delivery to another expert – the teacher. “…and remember, be sure to use your own words!”

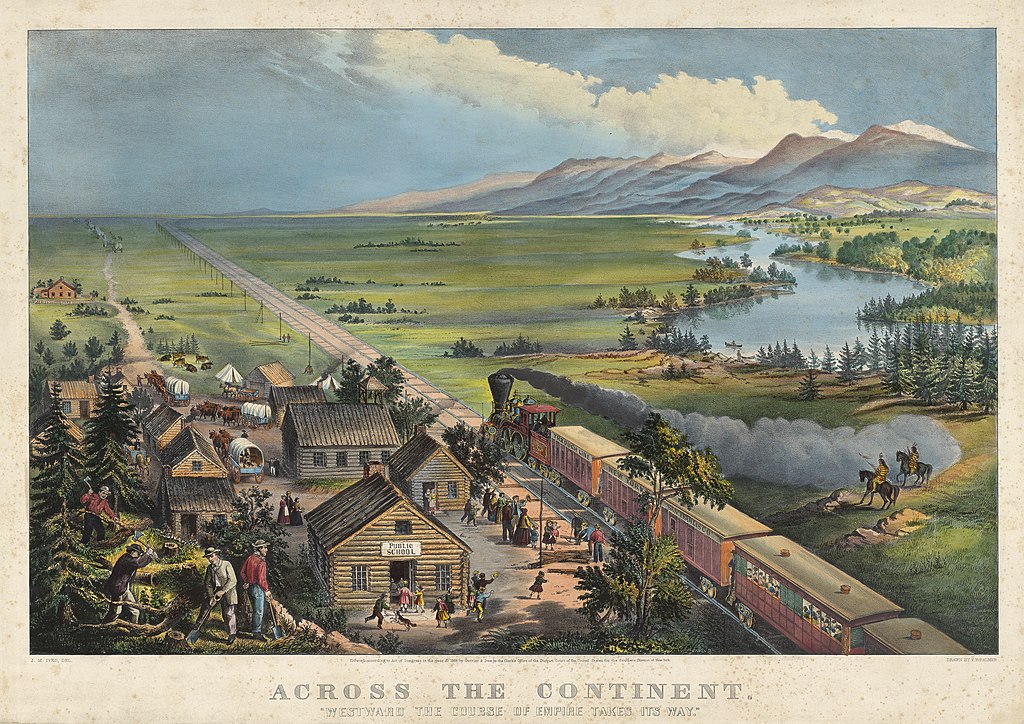

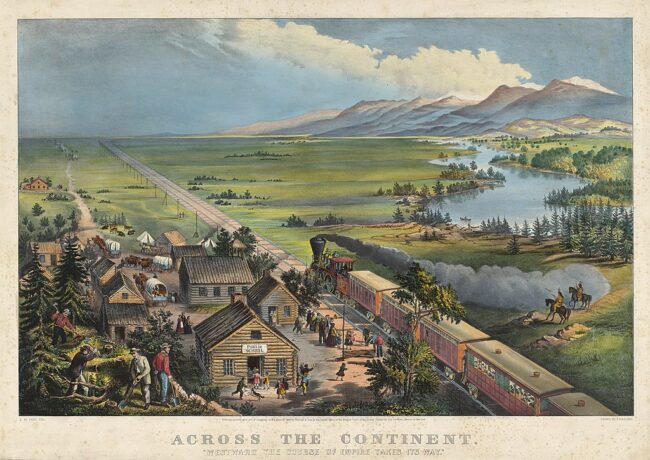

If students are going to learn to summarize they need to be given a chance to genuinely share what they think is important for an audience other than the teacher. Here’s a three step process I followed in a second grade classroom using a popular Currier and Ives print, “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way.” (1868) Link to larger image

Step 1: Start with the concrete “right there” observations.

I projected a digital image on the screen and asked student to talk about the people, things and activities they could identify. They replied, a train, native Americans, a village, people digging, steam from the train, houses, trees, a lake, maybe a harbor, a road, dry grass, covered wagons, poles, mountains, a school house, people working, people waiting for the train, a train track, etc ….

Step 2: Give students a chance to tell what they think is important.

I managed this aspect by asking each student to draw a picture of what they saw in the projected image. The details they included were what they thought was important. Here’s a few samples. Click to enlarge.

Step 3: Give students a chance to frame their summary into a narrative explanation for another audience.

I digitally divided the image into multiple sections and photocopied them (in B &W) into packets of image details. I gave groups of students the packets and asked them to work in teams to assemble the images into children’s “a story book” with a caption under each image.

Here are some of their captions: (spelling corrected)

- Water would come from the mountain and fill the lake. You could get fish and drink water. Water is very important

- People were moving west. They moved by wagon at first, then but train, which is faster.

- Life was tough. People had to do everything for themselves.

- It maybe was lonely because people missed their friends back home.

- The people were building a town. They could get wood from the trees. It was a small town at first.

- The Indian see the people coming. They knew things were changing. They got sick from the smoke.

- The school was different from our school. People had different clothes than us.

- The train split the old life from the new life.

While summarizing has been shown to be one of the most effective strategies for building content knowledge, that gain only applies when students are allowed to make their own judgements about what’s important and frame their summaries for an audience. When we ask them to “learn” the teacher’s summary – they are reduced to memorizing “another fact.”

When we ask our students to create authentic summaries (with audience and purpose) we give students a chance to reflect on their learning. Instead of simply testing them for factual knowledge, students can be asked:

- What did I think was important?

- How did I share that with my audience?

- Did my summary match audience and purpose?

- Is my summary accurate?

- Did I use my own words and style?

- What did I learn from the activity?

For more learning strategies see my blog post: 18 Literacy Strategies for Struggling Readers – Defining, Summarizing and Comparing