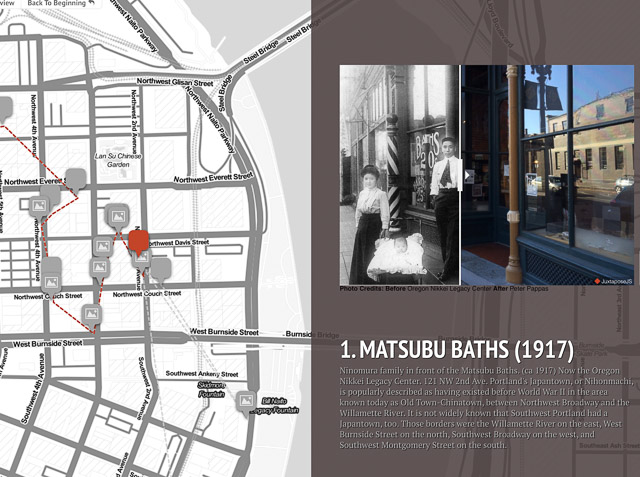

Northwestern University Knight Lab has produced some great free storytelling tools. I’ve previously posted about comparing images using JuxtaposeJS. It’s great for telling then and now stories when you have a good balance of continuity and change. Here’s a example of frame comparison I made using the tool. Use your mouse to grab the slider and move it up and down.

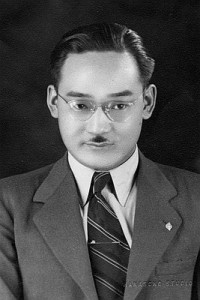

It shows one of Portland’s Japanese owned/managed hotels back in the heyday of Portland’s Japantown before the forceable removal and incarceration of its citizens during WWII. More on how to create with JuxtaposeJS

I had lots of great content from my multi-touch book Portland’s Japantown Revealed. It featured engaging then / now photo widgets that allow the user to “paint” history into contemporary photos with a wipe of their finger. So I reused the then / now photo comparisons using the a different tool – JuxtaposeJS and then used them for image content in the StoryMap. Note: Historic images are supplied by Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center. I took the contemporary photos.

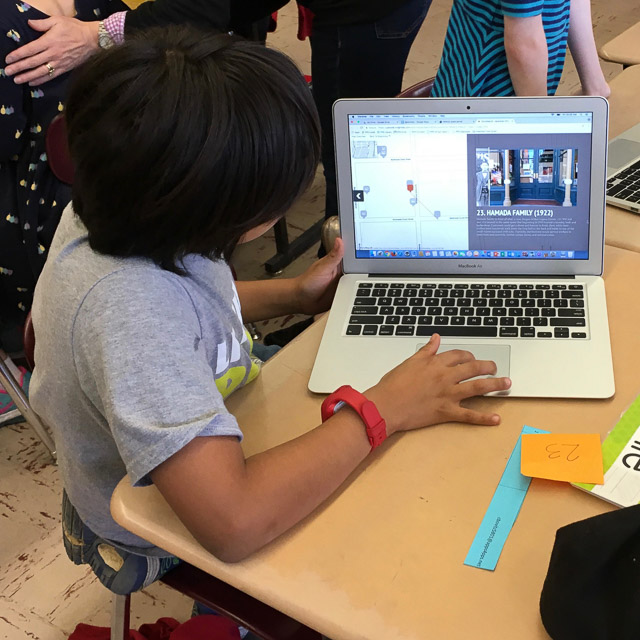

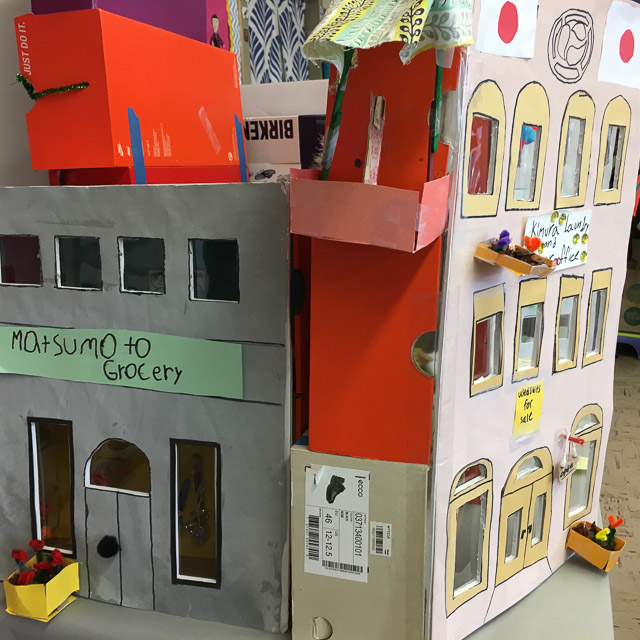

Backstory: I was scheduled to visit Marisa Hirata’s 3rd graders at Portland’s Alameda Elementary School. Students had been researching Portland’s Japantown and had already designed a “shoebox” replica of the community. For my visit, I created this StoryMapJS “tour” and the students used each stop as writing prompts. This StoryMap was great for helping students to visualize how people’s lives were lived in Portland’s thriving pre-WWII “Nihonmachi.”