We’ve all grown accustomed to turning to search engines when struggling to remember a detail or fact. But recently I found myself in a situation where “Googling” was useless. I was trying to recall a work of art without knowing the artist, title, or even the country of origin.

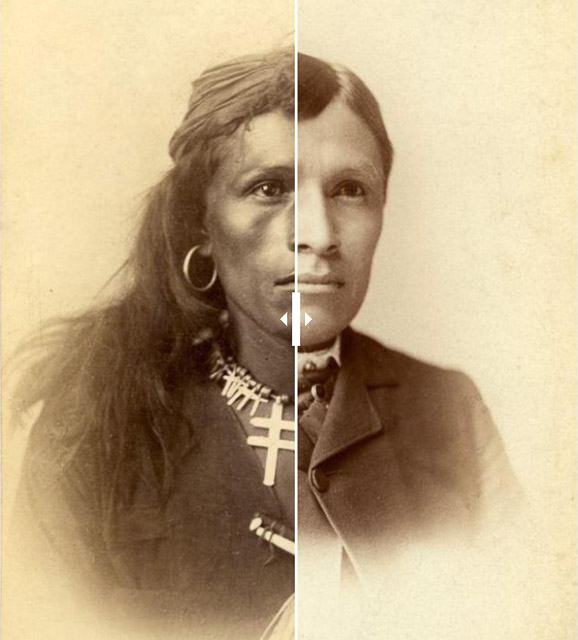

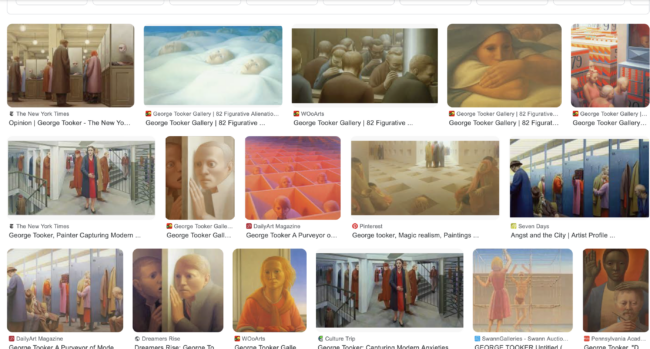

Note: At some point in my life I had seen George Tooker’s “Government Bureau” (1956) – a striking image (above) that had burrowed into my memory. But I lacked the descriptors that would work in a traditional text-based search.

Armed with nothing but a vague sense of the era and the artwork’s elusive “feel,” I turned to Meta AI for assistance. What followed was a bit magical—a journey through memory cubicles that led me to the masterpiece I sought.

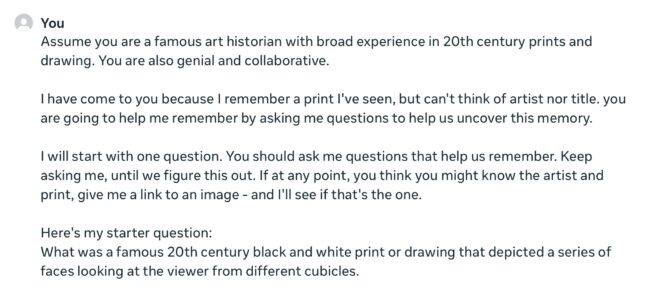

It began with this prompt

You’ll notice that my prompt tells Meta AI “who it is.” That’s a critical step in getting any AI to approach the task from a more specified perspective.

Next, I outlined the Q and A process we would use. This was essential, since I wanted the AI to ask follow up questions to narrow in on a solution. For fun, I gave it a bit personality – “genial and collaborative.” Also note that I incorrectly say it’s a black and white image.

Here’s a screenshots of Meta AI’s first response- the questions were logical – style, time period and where I might have seen it.

My response gave a date range but really focused on how the “feel” of the image in my memory – I said “Eastern European Kafka-esque bureaucratic workplace.”

In its second response, Meta AI noted my “Kafka-esque vibe” (a clever rephrasing). It pointed me to artists like Grosz and Dix. (I checked those artists and didn’t see any possibilities) And it posed a few more questions on how I remembered the faces and tone.

The best I could recall about the faces was they were blank and fearful. I added that the faces were “realistic with an overlay of artistic enhancement.” (Not the best description I’ve ever crafted.)

By Meta AI’s third response, it had correctly identified Tooker as a possibility.

I suddenly remembered the artist and asked to see some samples. Meta AI then pointed me to Google search of Tooker works (below) and there it was in upper left.

I was so impressed, I congratulated Meta AI for solving my query in such short order. It seemed like the thing to do. After some pleasantries, we signed off.

Comparing AIs

After this success with Meta AI, I thought I’d try the same prompt with other leading AIs. Note: I pretended not to know the answer and kept my responses limited to just the information I gave to Meta AI on the first run.

I was using the free versions. Here’s how they compared:

- Meta AI (above)- Identified artist in 3rd response and linked to “Government Bureau” in 4th.

- MicroSoft CoPilot – Identified artist and suggested it might be “Government Bureau” in 3rd response.

- Anthropic Claude – On it’s 9th response, it mentions Tooker but hallucinated a title he did not create.

- Google Gemini – Keeps suggesting artists and on 6th response, it gave up and wished me luck.

- Perplexity – gives up after 5th response. (But it did begin with a fun opening response: “clears throat and adjusts monocle. Ah, I believe I may know the work you are describing, my dear fellow! Let me ask you a few questions to jog your memory”

- ChatGPT 3.5 – patiently guessed and seemed to get closer to style. But I quit after 11th response when its suggestions began to drift off track.

Here’s why AI beats a traditional search engine in this use case:

A traditional search engine like Google relies heavily on keywords and metadata. When you search for an image, it looks for matches based on text associated with images across the web, such as titles, descriptions, tags, and other textual content. This means you need to have some specific information or keywords related to the image to start your search.

AI-driven image retrieval systems use machine learning algorithms to understand the content of the images themselves. They can analyze visual elements such as color, shape, texture, and even abstract concepts like the emotion an image might evoke. This allows them to find matches based on visual similarity rather than relying solely on text descriptors.

So, if you’re using AI for this purpose, you don’t necessarily need to know specific details about the artwork. You can provide a description of what you remember, and the AI can interpret that description to find images that are visually similar to what you’re describing. It’s a more intuitive process that mimics the way humans might try to find something based on vague recollections, rather than the precise keyword matching used by traditional search engines