xkcd’s brilliant mockery of the explosion of “info-junk” (at left) should remind us that the best infographics should efficiently combine quantitative data, prompt pattern recognition and cogent visual storytelling.

Perhaps aspiring infographic designers would do well to revisit the work of the Edward Tufte, the guru of the art form. I’ve had a chance to attend one of his inspiring workshops, but you easily appreciate his thinking from his books. In his classic “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information,” he lays out his principles of Graphical Excellence (p 51) Graphical excellence is:

- well-designed presentation of interaction data – a matter of substance, statistics and design.

- consists of complex ideas communicated with clarity, precision and efficiency.

- that which gives the viewer the greatest number of ideas in the shortest time with the least ink in the smallest space.

- always multivariate.

- requires telling the truth about data.

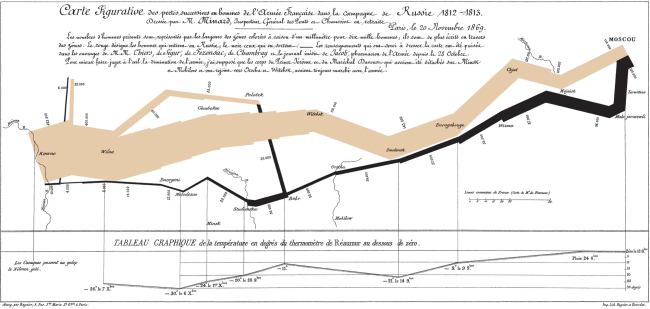

In the same book he showcases what he feels to be the best narrative graphic of space and time – Charles Joseph Minard representation of Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812. Six variable are plotted – the size of the army, it’s location on a two-dimensional surface, direction of the army’s movement, and temperatures on various dates during the retreat from Moscow. The comparative sizes of Napoleon’s invading army (in tan) to his meager retreating forces (in black) tell the story with eloquence.