I assigned my preservice teachers at University of Portland the task of using Learnist to design a document based question that would eventually become part of a class-produced DBQ iBook collection. DBQ assignment here. More samples of student-designed DBQs here.

I’ve asked them to reflect on the assignment and invited them to guest post on my blog.

First up is Red Scare DBQ designed by Christina Steiner & Kristi Convissor.

See Christina and Kristi’s chapter in our class-designed iBook – free at iTunes

You can find Christina at LinkedIn and here’s her posts on our class blog.

Christina Steiner reflects on what she learned from the experience:

“A few weeks ago Kristi Convissor and I started creating a DBQ project. We first started with a general outline the DBQ would take. We asked ourselves “What do we want students to learn from the DBQ overall?” To answer that we came up with a generative question to help guide our designing processing and to help the students when they are using the DBQ. The generative question was: “How does a nation develop such an intense fear and enmity that it creates mass hysteria?”

“From there we narrowed it down to look specifically at the Red Scare in 1950s America. We wanted students to learn about Americans fear of communism during the time. We wanted students to not only be aware of the hysteria but to understand where that fear developed from. One of the goals of the DBQ was to get students to think about what kind of words, actions, depictions lead to fear and what kind of outlets are needed to create mass hysteria. If students understand that then they can see how the Red Scare came to encapsulate so much of the 1950s.The design of DBQs lends well to this kind of investigation.

One of the goals of the DBQ was to get students to think about what kind of words, actions, depictions lead to fear …

When creating the DBQ, we chose documents that helped answer the generative question. We had found some cool documents, but they side tracked too far from our question, so we cut them. Having the generative question kept us focused on the main point of the DBQ. In addition we also created follow-up question to each document, which helped us pick quality documents. If the document could only address one question then it probably was not the best source we could use. We made sure to use sources that could be asked several questions because they held a decent amount of information in them for students to discover.

Our DBQ took a media lens to the issue

The final project which can be found on Learnist and soon on an iBook, met our goals. Our DBQ allows students to see for themselves how America came to have such an intense fear of communism through films, articles, and posters. Our DBQ took a media lens to the issue, examining the creation of an enemy based on characterizations rather than on facts or true events.”

Kristi Convissor reflects on what she learned from the experience:

See Kristi’s posts on our class blog.

Christina Steiner and I have been working on this project for several weeks. We started out with the idea that propaganda is meant to stir feelings in a certain direction, bad or good. Then we decided that we wanted students to recognize the use of propaganda throughout history. Our general question was “What do we want students to learn from the DBQ overall?” The generative question that we formed out of this starting idea was: “How does a nation develop such an intense fear of an enemy, creating mass hysteria?”

We thought that a good starting point to understand such hysteria would be the Red Scare in 1950′s America. We wanted students to learn about the paralyzing fear of communism that existed among Americans at that time. We wanted students to understand what caused such terror to develop. We wanted students to think about what words, images, actions, and depictions might cause fear and what is needed to cause mass hysteria. Student will then be able to understand the driving force of the Red Scare in 1950′s America. The DBQ slowly leads students to think in an investigative manner.

The DBQ slowly leads students to think in an investigative manner.

Christina and I chose documents that would help answer the generative question. We found A LOT of interesting documents and images, but we tried to stick to those that would answer that generative question. This kept us focused on the task at hand. We also ended each document or image with follow-up questions, to scaffold student understanding of propaganda. We wanted each document or image to provide a great deal of information that could lead to greater student discovery and interaction with each piece.

The final project can be found on Learnist and will soon be part of a larger iBook. Through this project, students will come to see and learn how America held such great fear of communism though images, books, comics, films, and posters. We looked specifically at media, examining the creation of enemies based on common perceptions rather than true events or facts.

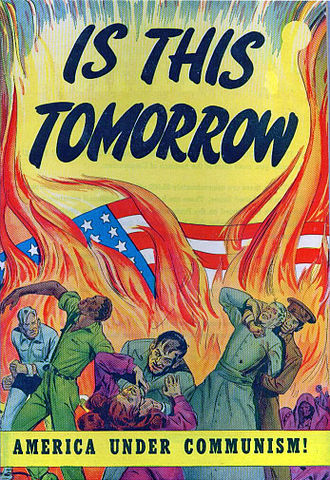

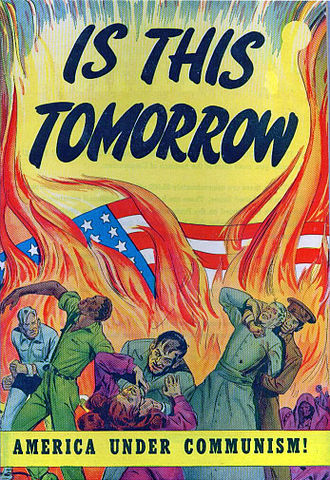

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Cover to the propaganda comic book “Is This Tomorrow”‘

Date 1947

Source Catechetical Guild

Like this:

Like Loading...

The NY Times Learning Network has just launched a new series of lesson plans called “Text to Text.” It’s a simple approach that pairs two written texts that “speak to each other.” I think it’s a Common Core close reading strategy that could be easily replicated by teachers across the curriculum – great way to blend nonfiction with fiction and incorporate a variety of media with written text.

The NY Times Learning Network has just launched a new series of lesson plans called “Text to Text.” It’s a simple approach that pairs two written texts that “speak to each other.” I think it’s a Common Core close reading strategy that could be easily replicated by teachers across the curriculum – great way to blend nonfiction with fiction and incorporate a variety of media with written text.

I just registered with the

I just registered with the