While many are aware that the US government forcibly removed and incarcerated more than 120,000 U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry during WWII. Few people know that the government recruited some of these same people to work at farm labor camps across the west to harvest crops essential to the war effort.

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II is a traveling photography exhibit (and website) that tells this story and provides a treasure trove of resources for historians, teachers and students. Uprooted draws from images of Japanese American farm labor camps taken by Russell Lee in the summer of 1942. Lee worked as a staff photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a federal agency that between 1935 and 1944 produced approximately 175,000 black-and-white film negatives and 1,600 color photographs.

Many are familiar with the work of Lee’s colleague Dorothea Lange, who worked for the War Relocation Authority in 1942. Lee also made significant contributions to the photographic record of the Nikkei wartime experience. Between April and August of 1942, he took some six hundred images of Japanese Americans in California, Oregon, and Idaho, including rare documentation of farm labor camps. To explore all of Lee’s FSA photographs, visit the Library of Congress website.

Uprooted also features video interviews with Japanese Americans who lived and worked in these seasonal farm labor camps as well as an archive of engaging historic documents from the era. Lee’s photographs depict smiling Japanese Americans cheerfully making the best of farm work and living in tents. But the interviews and historic documents tell a different story – harsh fieldwork, substandard living conditions and local townspeople suspicious of these intruders and their “questionable loyalty.” Even the incarcerated Japanese Americans were divided about working in the farm labor camps. Some saw it as an better alternative than the barbed wire of camps like Manzanar or Minidoka. But others resisted after hearing stories of grueling “stoop” labor, primitive housing and hostile locals.

While Uprooted focuses on a what some might consider a “footnote” of the US WWII homefront experience, I recognized that this rich collection could provide students with the material to develop historical thinking skills in sourcing, contextualizing, corroborating and close reading.

How does this collection of video interviews and historic documents help shed light on Lee’s intent? Was he trying to gloss over the harsh living and working conditions to help recruit more farm laborers? Was he trying to depict the noble and patriotic sacrifice of Japanese Americans forcibly stripped of their homes and livelihoods following the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese warplanes? Or did Lee simply shoot what he saw while on a photo assignment for the FSA?

I worked with the Uprooted team and developed a lesson How reliable are documentary photographs as a historic source? (1.1 Teachers Guide, 1.2 Photographs, 1.3 Documents) Students begin by reflecting on the photographs they take and often share on social media. What do you see in the photographs? What stories do they tell? Next they are taken through scaffolded activities to closely examine Lee’s photographs and compare them to the often conflicting depictions of the farm labor camps found in the other historic documents. Finally they are asked to reconsider their contemporary social media photographs and how they might be interpreted by future historian studying “the life of a teenager in 2010s.” A complete lesson plan, collection of images and historic documents is available at Uprooted. The site even includes a kit for students to curate their own Uprooted museum mini-exhibit. A second lesson plan is also available. How reliable are documentary films as a historic source? Lesson plan 2.

You can find Uprooted on Twitter | Facebook | Flickr | Instagram

The museum exhibit open at The Four Rivers Cultural Center in Ontario, OR on September 12, 2014 and runs through December 12, 2014. It then travels to Minidoka County (ID) Historical Society and the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center in Portland Ore. More exhibit info and updates

I’d like to close this post by crediting the talented team behind Uprooted. Curator – Morgen Young, Web and Graphics Designer – Melissa Delzio, Videographers - Courtney Hermann and Kerribeth Elliott. Uprooted is a project of the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission.

Top Image credit: Library of Congress

Title: Los Angeles, California. The evacuation of Japanese-Americans from West Coast areas under U.S. Army war emergency order. Japanese-American family waiting for train to take them to Owens Valley

Creator(s): Lee, Russell, 1903-1986, photographer

Date Created/Published: 1942 Apr.

Medium: 1 negative : nitrate ; 35 mm.

Reproduction Number: LC-USF33-013296-M4

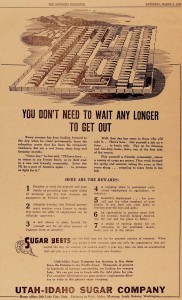

Newspaper Ad “You don’t need to wait any longer to get out.” From the Minidoka Irrigator.

Sugar companies posted recruitment notices and advertisements in public spaces throughout the camps, as well as in camp newspapers. Such advertisements emphasized seasonal labor as an opportunity to leave confines of camp, but also marketed the work as the patriotic duty of Japanese Americans, ignoring that they had been incarcerated and denied their civil liberties.

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., Record Group 210, War Relocation Authority.

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column

I recently was a contributor to a Education Week Teacher’s “Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo” column

I assigned my preservice teachers at University of Portland the task of using

I assigned my preservice teachers at University of Portland the task of using