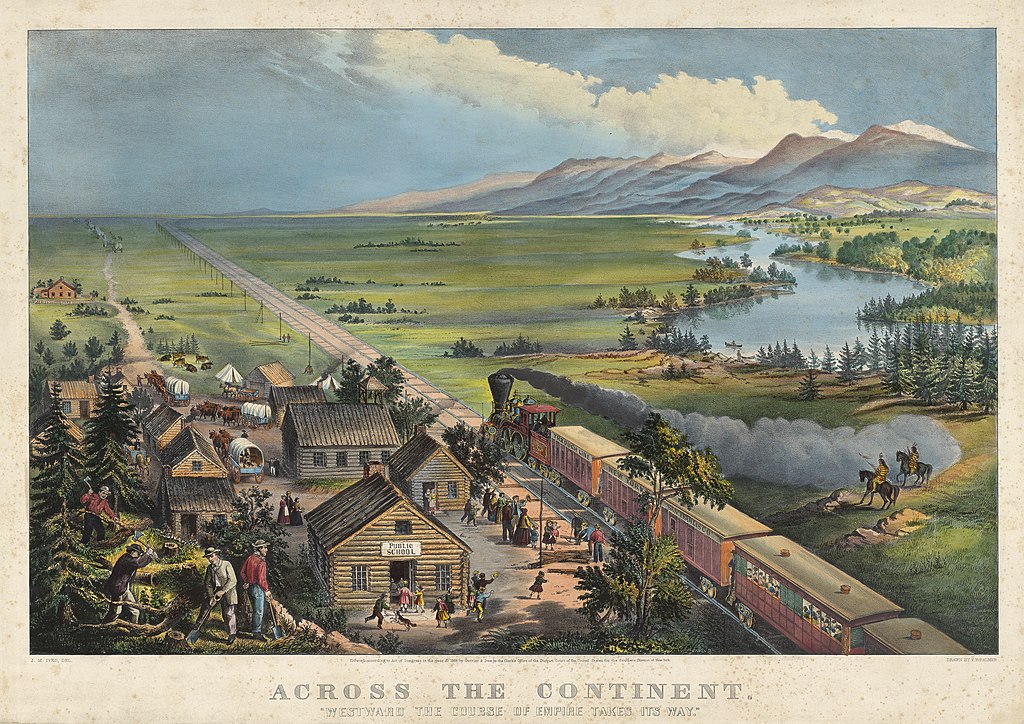

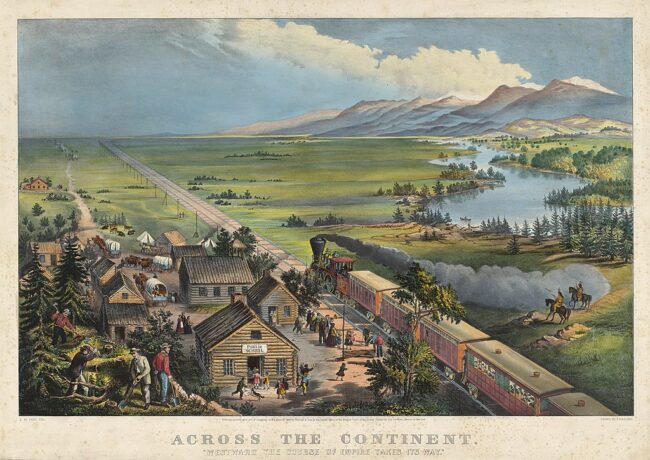

reflective student

Reflection can be a challenging endeavor. It’s not something that’s fostered in school – typically someone else tells you how you’re doing! At best, students can narrate what they did, but have trouble thinking abstractly about their learning – patterns, connections and progress.

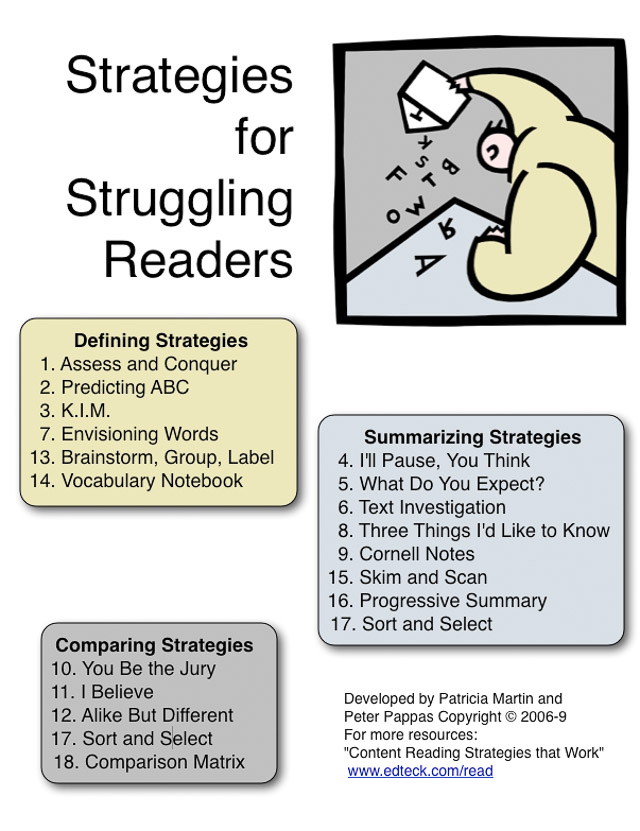

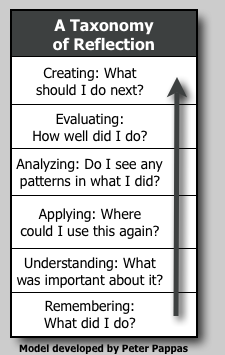

In an effort to help schools become more reflective learning environments, I’ve developed this “Taxonomy of Reflection” – modeled on Bloom’s approach. It’s posted in four installments:

1. A Taxonomy of Reflection

2. The Reflective Student

3. The Reflective Teacher

4. The Reflective Principal

See my Prezi tour of the Taxonomy

2. The Reflective Student

Each level of reflection is structured to parallel Bloom’s taxonomy. (See installment 1 for more on the model). Assume that a student looked back on a project or assignment they had completed. What sample questions might they ask themselves as they move from lower to higher order reflection? (Note: I’m not suggesting that all questions are asked after every project – feel free to pick a few that work for you.) Remember that each level can be used to support mastery of the new Common Core standards.

taxonomy of reflection

Bloom’s Remembering: What did I do?

Student Reflection: What was the assignment? When was it due? Did I get it turned in on time?

Bloom’s Understanding: What was important about what I did? Did I meet my goals?

Student Reflection: Do I understand the parts of the assignment and how they connect? Did my response completely cover all parts of the assignment? Do I see where this fits in with what we are studying?

Bloom’s Application: When did I do this before? Where could I use this again?

Student Reflection: How was this assignment similar to other assignments? (in this course or others). Do I see connections in either content, product or process? Are there ways to adapt it to other assignments? Where could I use this (content, product or process) my life?

Bloom’s Analysis: Do I see any patterns or relationships in what I did?

Student Reflection: Were the strategies, skills and procedures I used effective for this assignment? Do I see any patterns in how I approached my work – such as following an outline, keeping to deadlines? What were the results of the approach I used – was it efficient, or could I have eliminated or reorganized steps?

Bloom’s Evaluation: How well did I do? What worked? What do I need to improve?

Student Reflection: What are we learning and is it important? Did I do an effective job of communicating my learning to others? What have I learned about my strengths and my areas in need of improvement? How am I progressing as a learner?

Bloom’s Creation: What should I do next? What’s my plan / design?

Student Reflection: How can I best use my strengths to improve? What steps should I take or resources should I use to meet my challenges? What suggestions do I have for my teacher or my peers to improve our learning environment? How can I adapt this content or skill to make a difference in my life?

Image credit: flickr/Daveybot

Recently my post:

Recently my post: