Teach in the Block

I’ve been preparing for an upcoming two day workshop at Nassau County SD (FL) – assisting high school teacher with strategies for teaching in a block schedule. It got me thinking about my attitude about class length and how my perspective evolved as my instructional vision changed.

When I first started teaching high school social studies the central planning question I asked myself was, “What am I going to do with my students?” The focus was on my activities, because I thought my job was to convey information to my students – to tell them things they didn’t know. Then they could practice working on what I told them. Finally my students could prove they “got the things” by giving me back what I gave them on a test. Thus my curriculum planning centered about how I was going to deliver the information to them. I had a lot of information to cover and had to figure out how to cut it up into 180 bites. “This year I hope we can at least get to WWII!”

Seen from the “lecture” perspective, I liked short classes – holding the attention of 30 high school kids was a challenge. I remember when our class periods got cut from 48 minutes to 45, I thought – great, now I don’t have to talk as long. I can shave a few minutes off my delivery.

When I first started teaching, the question I repeatedly asked myself was, “What am I going to do with my students?” The focus was on my activities, because I thought my job was to convey information to my students – to tell them things they didn’t know.

After a few years of lecturing, I had the realization that I was the hardest working person in my class. I was doing most of the learning – research, analysis, synthesis and preparation of summaries to share with my students. And so I began the long journey of redefining my role as teacher from “teacher as talker” to “teacher as designer of learning environments.” I had to figure out how to create situations where my students could “research, analyze, synthesize and prepare summaries” to share with audiences (other than me). And as I made the transition, I longed for longer blocks of instructional time. I found that students needed time to decide how to approach a task, trouble shoot their approach, execute their plan, present what they learned and reflect on how it went.

Thus I learned the first lesson of transitioning to the block schedule. Don’t ask teachers who lecture to suddenly work in a block schedule – get teachers comfortable with student-centered learning and wait for them to demand longer class periods. In other words, instructional vision precedes organizational tinkering. (Later as an assistant superintendent, I put that lesson to good use.)

So how will I structure this week’s block scheduling workshops ? For starters I won’t spend the day talking at them. Of course, teachers will want specific strategies they can use. While I will share many approaches, the workshop has to be more than a collection of lesson ideas. That’s too much like my early method of teaching – me simply delivering information. Besides I won’t be the smartest person in the room.

Staff development should model what you want to see in the classroom. As Donald Finkel has written, teaching is “providing experience, provoking reflection.” My goal will be to give the teachers the experience of transitioning through a variety of learning situations of varying lengths. I want them to see the learning strategies in action and get a feel for how their level engagement can impact their sense of passage of time. I want them to leave with more than teaching ideas. I hope to provoke their ongoing reflection on what happens when students have more time to take ownership of the content, process and evaluation of their learning.

Like this:

Like Loading...

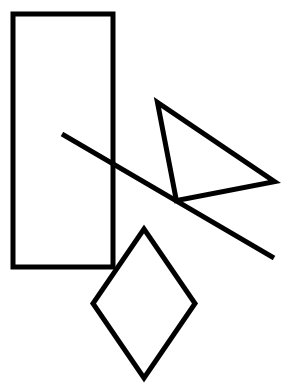

3. For our last activity, I gave a teacher volunteer a simple diagram. See sample diagram at left. I asked them to instruct the rest of the group how to draw it.

3. For our last activity, I gave a teacher volunteer a simple diagram. See sample diagram at left. I asked them to instruct the rest of the group how to draw it.