My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Fourth of 13)

My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Fourth of 13)

The Samurai: Sources of Warrior Identity in Medieval Japan by Benjamin Heebner

Download as PDF 1.8MB

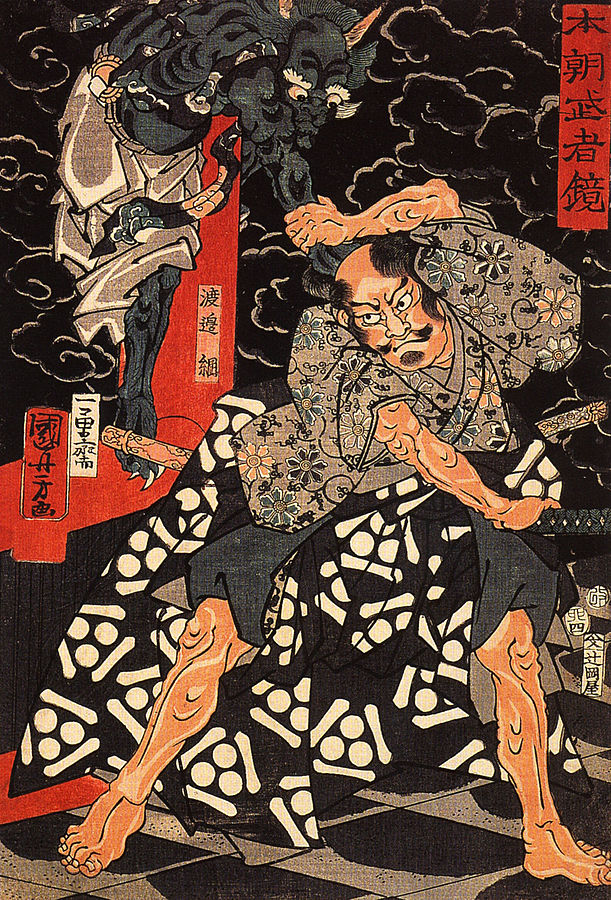

This document based lesson will use Medieval depictions of the Samurai to answer the question of what it means to be a warrior in Japan and the place of the warrior in society. This lesson, is aimed for students to think about how warriors were romanticized in Japan, and how the social structure of Japan reinforces these depictions. in addition, students will then use these understandings see how Medieval Japanese society was ordered.

- What does being a warrior entail?

- How are warriors identified?

- Are the depictions of warriors truthful or are they fabricated?

Reflection by Ben Heebner

The topic of my document-based lesson project is Japanese warrior identity as shown by Medieval era (1185-1868) depictions of warriors. In the lesson students are asked scaffolding questions that help them look at the underlying biases that go into the varied depictions that we are looking at. By doing this students will be interacting with the sourcing of documents, while forming a contextualization of the time period and society that had its top class dominated by warriors. Using the sources that I chose, students will be able to engage in the question of how groups of people are depicted and why these depictions and the truth may not actually match up. I intentional choose semi-historical depictions of the Samurai to showcase how depictions reflect the identity of the time period that they were created in.

From the first step in creating this document based lesson I knew that I wanted to do something with Medieval Japan. My mind instantly thought about the many woodblock prints (Ukiyo-E) that became massively popular during the Edo Period of Japanese History (1615-1868). By paring these more recent images of warriors and events, that were popularized by the war tale genre, with the war tales and their definition of valor and bravery, I felt that students would become engaged with this material readily. I knew that I would have to include a source from the war tales themselves to be able to tie all the images together so I picked the ending scene from the Hogen Monogatari. While the inclusion of more documents would help, I think that the depictions that I chose give students the chance to question why these documents were made and why these documents became so well known within Japanese society.

Medieval Japan is a secondary topic of study for most World History classes. The time devoted to Japan is either at the very end of the year, when teachers are looking to fill time, or as an aside to exploration of China. As this document based lesson shows, Japan’s Medieval period is filled with a gold mine of historical inquiry. Japan’s Medieval period is filled with a great many questions that reverberate across the entire world during the Medieval period. The one that this lesson focuses on is, What does it mean to be a warrior. by looking at this question students will have the opportunity to see how extremely different cultures view the same topics and begin to see how different cultures and groups respond to challenges. By engaging in these questions, students will have the opportunity to be junior historians and engage in the material the same way that a historian would.

At the end of the lesson I would have one of two activities. The first activity would be a standard argumentative essay that asks students to show me whether or not the depictions of Samurai offered up by the documents are justified or are they hiding the villainy of an entire group of people behind a facade of fiction. Another activity that could end out this unit would be for groups of students to create a movie poster for a fictional film that depicts Samurai. In doing this students would be asked to show whether or not their film would promote the Samurai or vilify them using the documents and depictions as a base. These two activities allow students to engage with the generative question of these lessons which is, what does it mean to be a warrior? In addition, the second activity allows students to display their understanding of the documents by depicting how the documents only show a side of the warrior class.

Image credit: Watanabe no Tsuna fighting with Ibaraki at the Rashomon gate, woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi Wikipedia