The Portland City Club is continuing its educational series Schools Making A Difference: Portraits of Excellence, Engagement and Equity – films, panel discussions and participant dialogues.

Though economic realities pose significant challenges for our education system, when schools and communities work together with a clear vision and heroic effort, they can achieve stunning results. Exemplary schools provide high expectations and opportunities for all students to succeed. They also provide real world learning experiences that prepare students for college, careers and citizenship in the 21st century. They do this through an engaging curriculum that recognizes the diverse talents and needs of their student populations. Join fellow citizens, educators, and students for any of four evenings of films, panels, and participant dialogues that offer portraits of such schools in our region and around the world.

The series continues Feb 8 at Mission Theater with a screening of Robert Compton’s “Two Million Minutes” followed by panel discussion. March 5th: “The Finland Phenomenon: Inside the World’s Most Surprising School System” by Robert Compton. (Hollywood Theater) The final forum is March 14 How Important Are the Arts and Civic Education for Our Students’ Current and Future Lives? featuring the film “Paper Clips” by Elliot Berlin & Joe Fab. (Hollywood Theater)

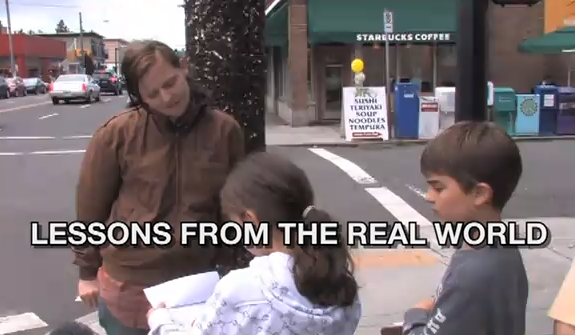

I attended the first session which featured the film Lessons from the Real World. Bob Gliner, filmmaker, as well as local educators offered an engaging follow up discussion with the audience. The film highlights project-based learning in greater Portland region schools. It’s a fascinating look at K-12 schools that weave community and societal problem solving through their curriculum.

Oregonians will have another chance to see the film which is screening on OPB Plus Sunday night, Feb. 12 at 7 PM throughout most of Oregon. More on “Lessons From the Real World”

Many people feel our public schools are failing, or at best, muddling through. What to do about this critical issue has almost exclusively focused on the efforts of No Child Left Behind and now Race to the Top legislation to improve test scores in core subjects like math and reading.

Lessons From the Real World, contends, like many educators, that focusing on test scores to improve student achievement is looking in the wrong place.

Learning to read, do math and other subjects will come if students care about what they are learning, rather than drilling them with subject matter largely divorced from their real lives, and the community and societal problems which often impact those lives.

In Portland, Oregon, teachers at a wide range of schools are putting this idea into practice. While this is their story, it can help point the way to rethinking how schools everywhere can be successfully transformed.