My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Fifth of 13)

My Social Studies Methods class at the University of Portland recently published a free multi-touch iBook – Exploring History: Vol III (free iTunes). It features thirteen engaging questions and historic documents that empower students to be the historian in the classroom. For more info on our project and free download of multi-touch iBook and pdf versions click here. To better publicize student work, I’m featuring each chapter in it’s own blog post. (Fifth of 13)

Finding Egyptian Needles in Western Haystacks by Heidi Kershner

Download as PDF 3.2MB

Essential Question: Who owns and has the right to cultural property?

Beginning with Roman rule in 31 BCE many of Egypt’s obelisks were transported throughout the empire to be set up in various cities. Because of this, the city of Rome now houses more obelisks than anywhere else in the world (including Egypt). Three such obelisks found their way to the metropolises of London, Paris, and New York in the nineteenth century.

Reflection by Heidi Kershner

The process of designing a document based lesson was quite lengthy and involved. It required finding not only relevant documents and primary sources but ones that were both rich enough yet easily accessible for students to engage with on a deep level.

In my case I found this objective fairly challenging as I was looking to create a lesson to fit within a unit about ancient Egypt. Given that the subject for my lesson was from such antiquity I found it fairly difficult to find primary sources and other documents that would fit the aforementioned stipulations. However once I was able to identify my documents the actual designing of the lesson was pretty fun!

Throughout this process I had to continually put myself in the shoes of my students and ask the question: what should students be doing and learning from each document? With this important question in mind I was able to critically think about how each document and primary source fit into the larger fabric of my lesson.

Even though this type of lesson carries a fairly heavy workload in terms of planning I think that this would be a fantastic method to use in my instruction. Certainly not every lesson can be document based but I think that such lessons could be very powerful in terms of both increasing student content mastery as well as providing an opportunity for students to act as historians (which should always be our goal as teachers of social studies)!

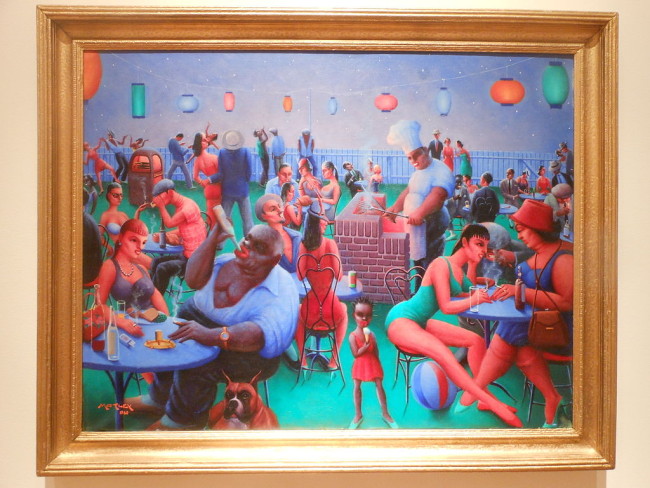

Image credit: Wikipedia

Cleopatra’s Needle in London seen from the River Thames. In the background the New Adelphi, a monumental Art Deco building designed by the firm of Collcutt & Hamp.in the 1930s.

Photographed by Adrian Pingstone in June 2005 and released to the public domain.