As teachers struggle to navigate the new landscape of the Covid classroom, I’m reminded of a Socratic seminar model I used years ago while teaching AP history and government. It blended instruction in both full class and smaller seminars in way that could be a useful model to decrease the density of today’s classroom.

What drove my seminar model was PBL approach with weekly research tasks – though I had yet to hear the term “project-based learning.” My experience using this approach back in the 1980-90’s convinced me that advanced placement can be much more productive than the traditional AP model of lecture, read, memorize and test.

While this seminar approach produced great results on AP exams, its prime outcome was fostering students’ responsibility for themselves as learners. Covid-19 is upending our traditional classroom models. Instead of simply trying to find news ways to deliver the same stuff, we should leverage this disruption to refocus teaching and learning in ways that engage and motivate both students and teachers.

The Socratic Seminar Model

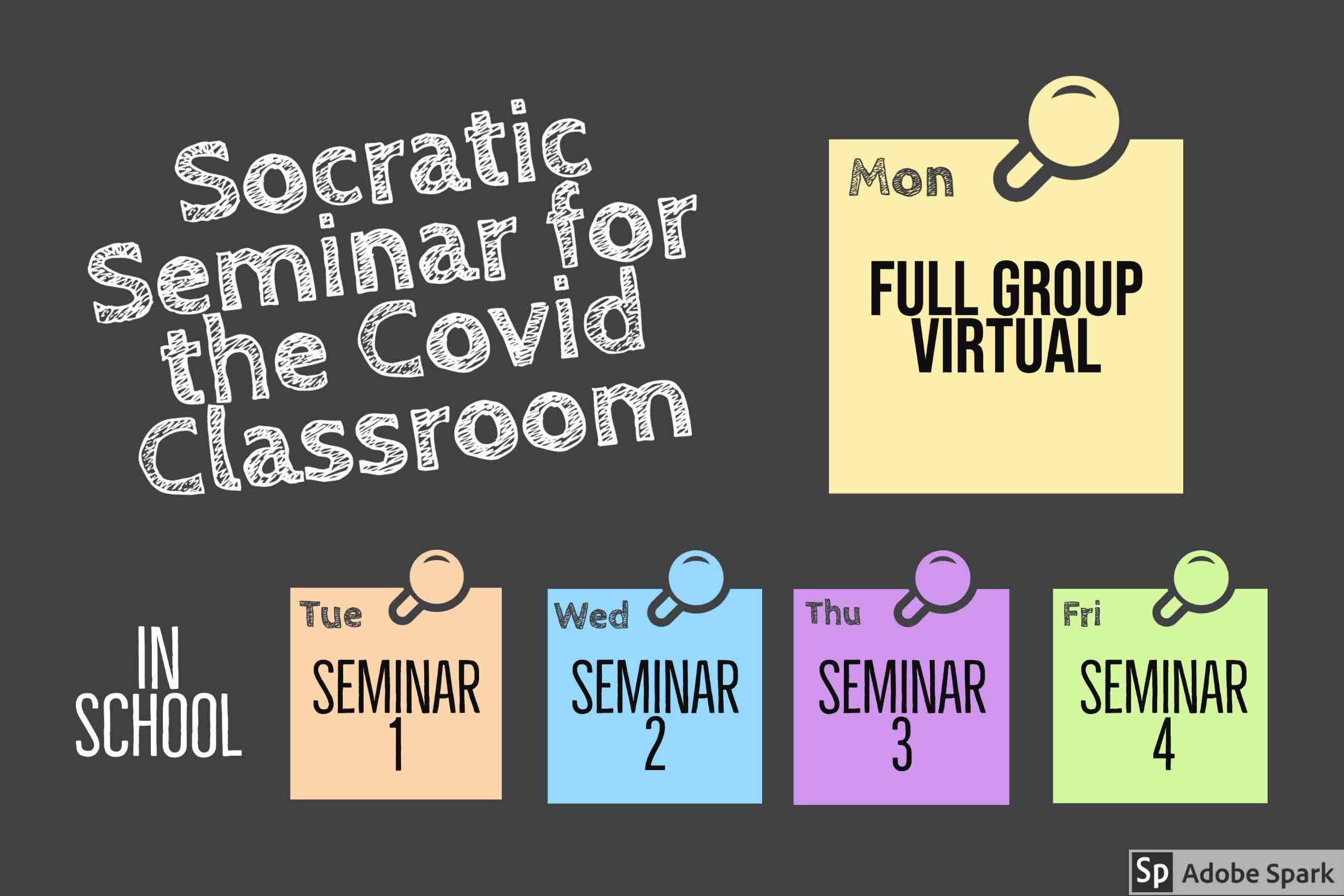

As we look for ways to blend virtual learning and meet live in smaller classes – this model could be modified by substituting an online session for the full class large group. Seminar size and frequency are adaptable to the setting.

Class size typically ran between 24 – 36 students. All students in the class would meet one day a week in a large group session. This might be used for unit testing, or to introduce or conclude a seminar cycle with a lecture or full group discussion. The large group was also divided into 4 seminar groups of 6-9 students. Each seminar would meet with me one day per week. Thus each student met one day per week in seminar and another day in large group. During the remainder of their week, students worked independently or with their seminar group in preparation for the upcoming assignment. Today, we would call that “flipping the classroom.”

Seminar assignments built off the large group session and were project driven. Students in the seminar were required to present and defend their finding to their peers. I sat “outside the circle” as an observer – occasionally tossing probing questions into the group.

Of course, there were many weeks that were modified because of holidays and other interruptions – but you get the idea. Our high school was on traditional 8 period schedule. These AP classes were taught in a double period configuration of about 95 minutes for both the seminar classes or large group sessions.

My first experience was teaching one semester of AP US History while one of my colleagues was on leave. I focused on essential questions that fostered greater depth and relevance. So when we studied the Founding Fathers we didn’t focus on “Should the Constitution be ratified?” Our seminar revolved around a more enduring question – “How powerful should the national government be?” For more on that approach, see my post “Essential Questions in American History: The Great Debates.”

After my semester of APUSH, I settled into my primary AP assignment – one semester of AP American Government / Politics and one semester of AP Comparative Government. There I used the seminar approach to give students guided experience in research, critical thinking, collaboration and presentation.

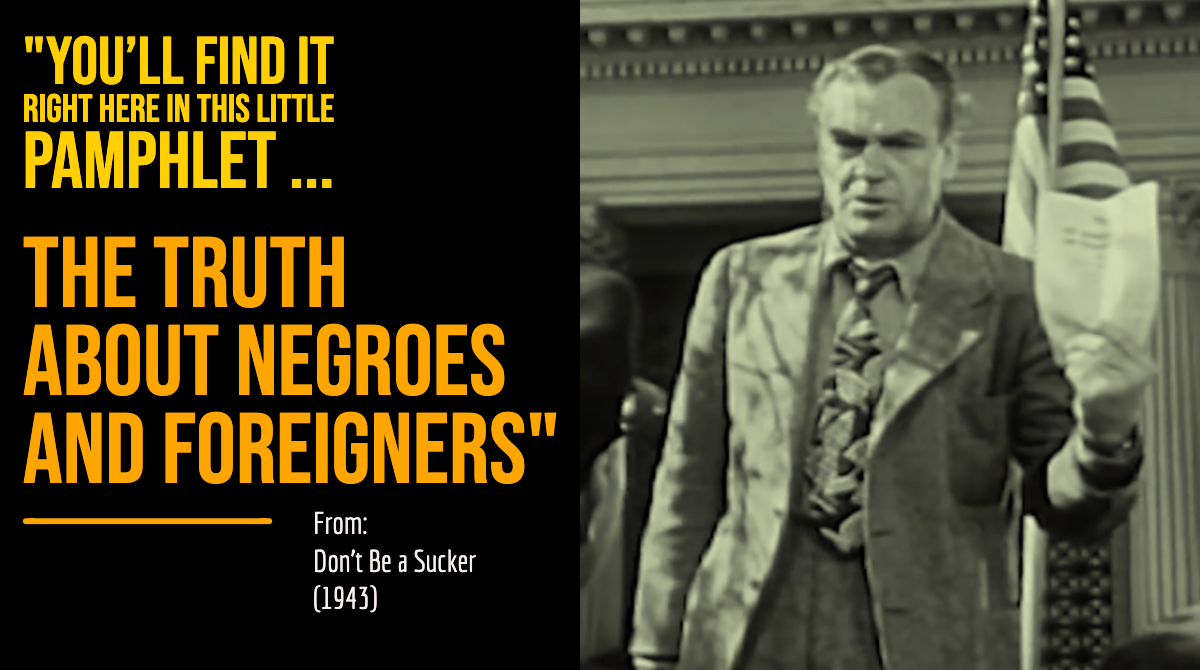

Visualize the typical American government lesson. Teacher standing up front asking students to follow along as they go over the diagram of “how a bill becomes a law.”

Contrast that with one of my AP US Government seminars on the same topic.

Congress and the Lobbyists

This extended seminar will investigate the relationships between Congress and the lobbyists. You will develop an investigative report which will ultimately answer the question “Does Congress represent the needs of its public constituency (the electorate) or its financial constituency (its contributors)? Weekly seminar abstracts will be used to prepare Tabloid TV-style PowerPoint report in support of your investigation. To see the full seminar assignment click here.

Students were assigned a member of Congress who sat on one of the major committees. Their task over the next few weeks included researching and developing the following:

- Demographic / political profile of their legislator’s elective constituency.

- Profile of their financial contributors.

- Committee jurisdiction and major lobbyists.

- Voting record on legislation of interest to their elective constituency and financial contributors.

- Their answer to the seminar question with supportive reasoning.

- Presentation and reflection